Commissioned Portraits

Commissioned portraits can be portraits that an individual person or an institution suggest I make. The person who requests a portrait can be someone who wishes their own portrait, a portrait of a family member, or of someone they admire.

Some portraits have been commissioned by a museum, such as The Invisible Body, a set of 26 portraits I made for Museum Wiesbaden or by a company, such as the 7 portraits I made for the atrium of the B-W Bank in Stuttgart. Some portraits are commissioned by collectors who have a special interest in an artist, say, Joseph Beuys or Kurt Schwitters. I do the research and make the portraits. Multiple portraits usually require a conceptual context, a framework that I develop. I like to make portraits directly for individuals. These are not for sale to people other than the person who commissioned the portrait and there are no editions. I have made anonymous portraits or portraits that are entirely private, unnamed names. I worked as a portrait photographer in the past, working for LIFE, STERN, many publications, companies, etc. My portraits of de Kooning were commissioned by The Akademie der Künste, Berlin and later included in retrospectives at the Whitney, MOMA, and various galleries. Now I make the portraits according to a different vision. Portraiture is an ancient genre, seen ever anew.

My Process

How I make a Portrait:

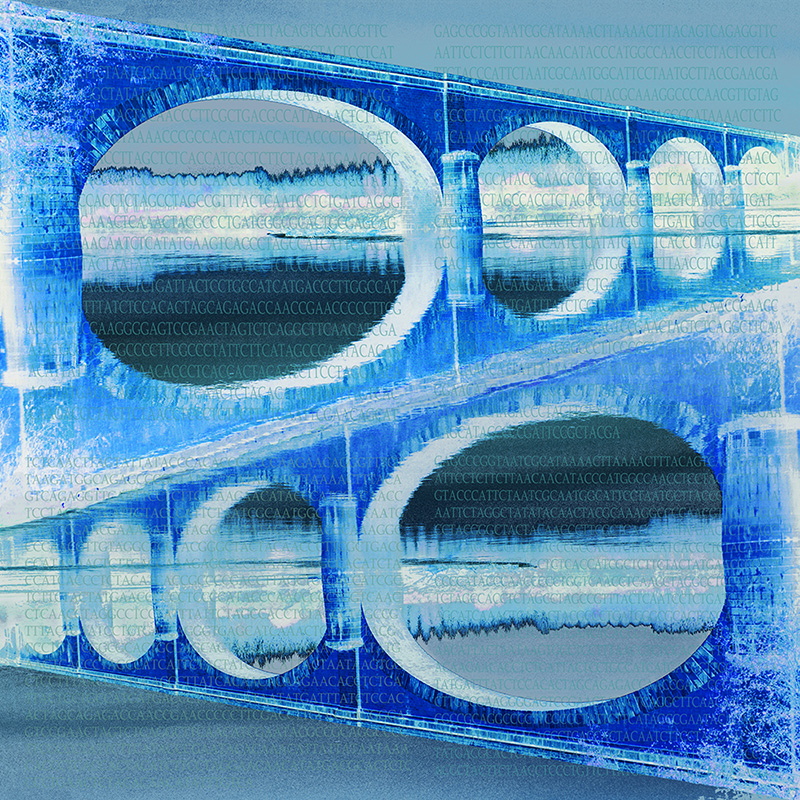

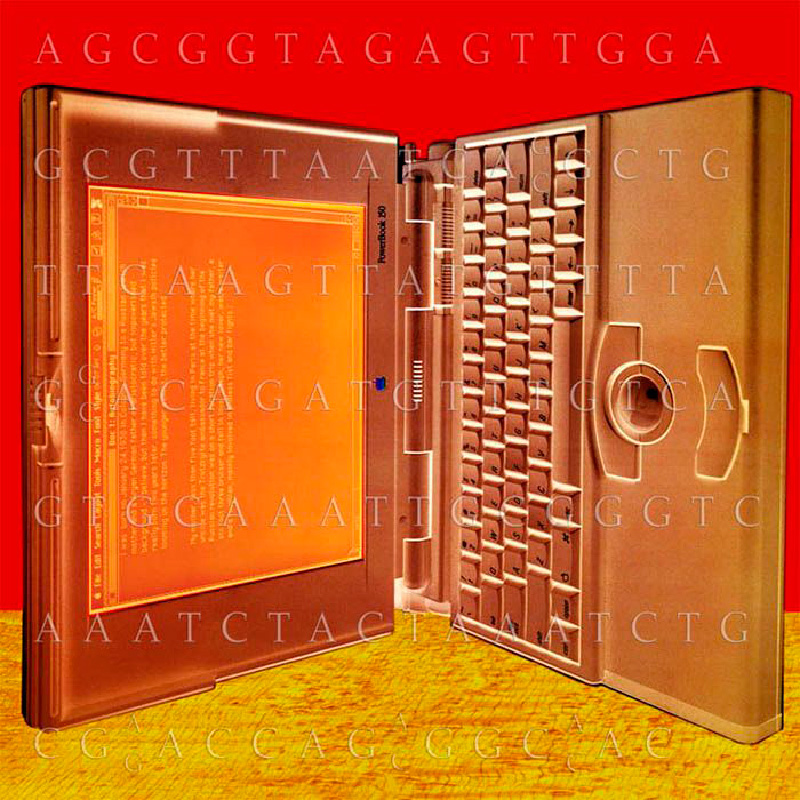

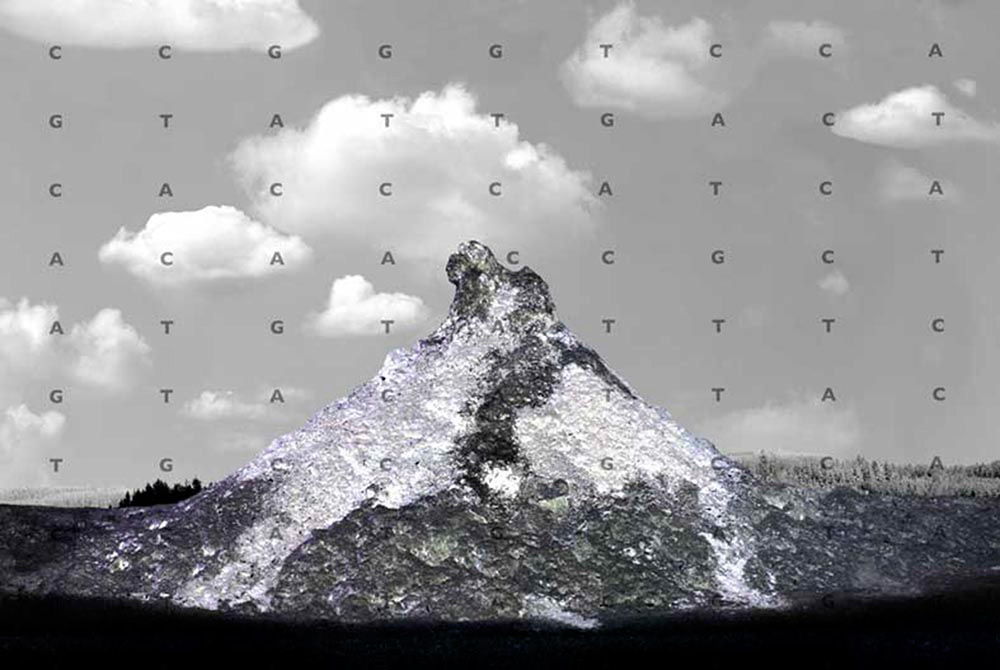

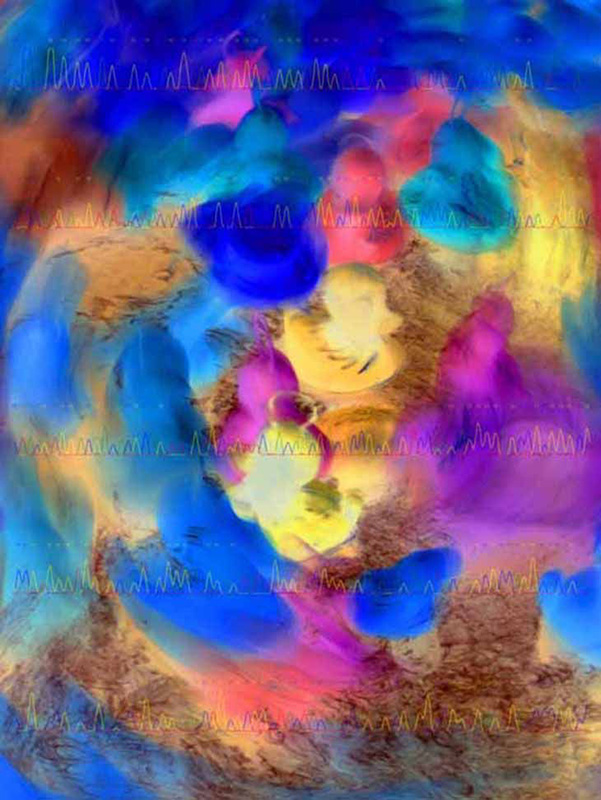

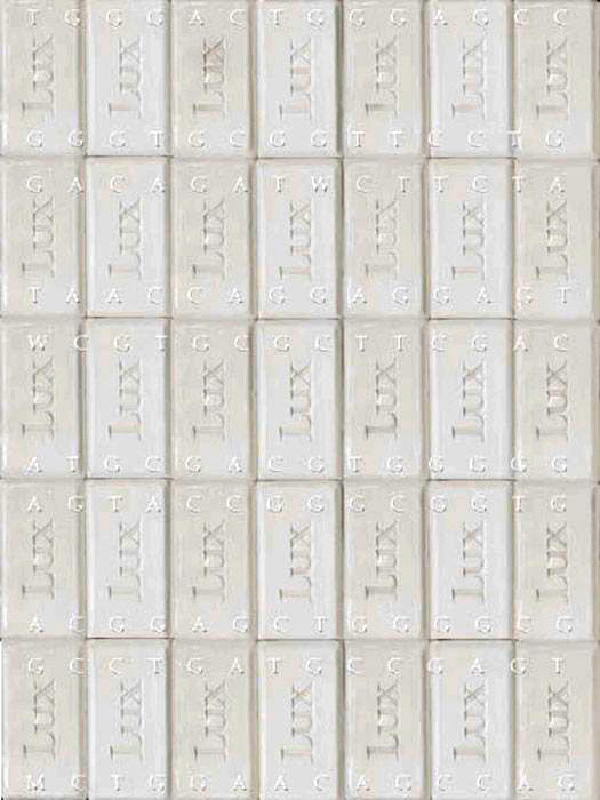

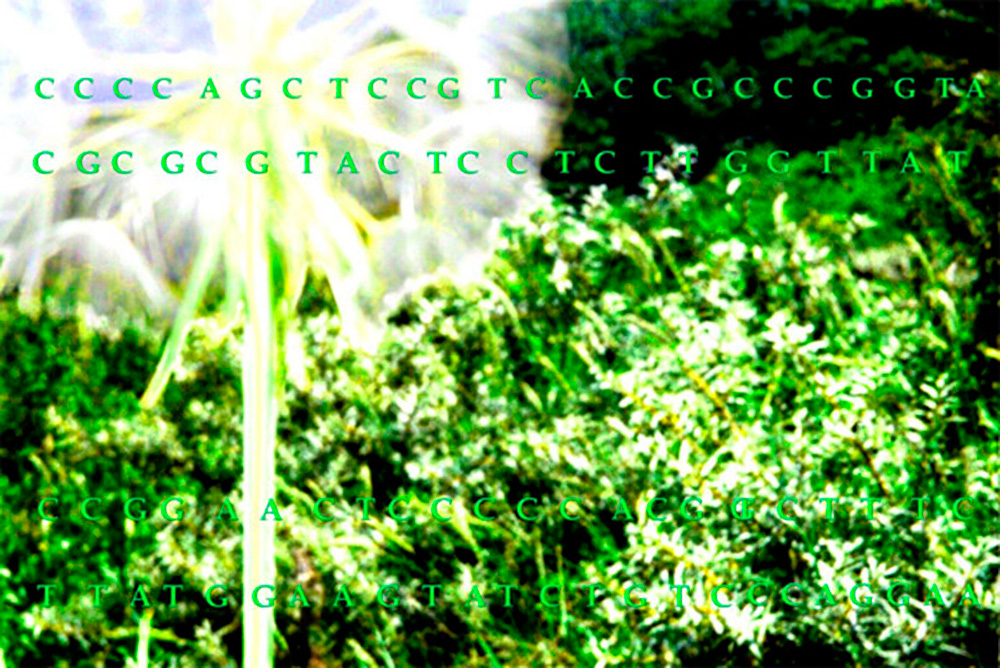

The person who is to be portrayed schedules a first visit, and I spend some time with them. I ask questions, but they are not about heredity and they are not indiscrete or overly personal. I try to understand something about the person, get a sense of who that person is. This happens in an indirect way, not rationally, with feeling. Several visits ensue. I then need either a buccal swab (a Q-Tip rubbed on the cheek) or a few hairs, gently removed with the tiny root attached. This takes a second and is painless. The hairs or Q-Tips are sent to the DNA lab with a code that I write on the sample container so that the person’s privacy is 100% ensured. The lab sequences the DNA and a representation in graph and letter form is produced using special software I helped develop. After reflecting, I create a photographic image, which I work on and combine with the letters or the graphic expression of the DNA. Sometimes the image is a landscape, an object, a collage I make with a few elements, or with themes I introduce. This forms the original image, a negative on film or a digital file from which the photographic enlargement is made.

Recent DNA Commissions

Paper Title: Kevin Clarke:

Artist talk.

I am here to present my portrait commissions, especially my most recent interpretative DNA portraits, and to show you a selection of related prior works beginning with the 1991-1995 series From The Blood of Poets, Taken, Literally.

Working within a classic genre, I would like to explore the contradictory nature of adhering to and being insubordinate to traditions inherent in the communication paths that include the relationships and conventions marked by the terms artist/sitter/public.

The initial public reaction to my work has sometimes been one of a distancing, a feeling that the notion that a person can be portrayed by their invisible aspects, and through pictorial means ignoring the physical in it’s most obvious form, mocks the entire enterprise of portraiture. Yet mockery, a currency which so profoundly underpins our time, is not at all present in my interactions with the men and women I make portraits of, nor in the final images, though I sometimes aim for a lightness which can be confused with humor.

I’ve happily dispensed with mockery in this work, and have tried to connect with and discover something about the person I am making a portrait of and with. The portrait begins with the subject giving me a blood sample or a few hairs, a swab. There is a conscious giving. When I hosted happenings during which my friend the nurse Reiko Saito took blood samples from my subjects, or sitters, I called them Drawings.

It is the communication and set of interactions with the sitter, who is not as passively involved as the term implies, which form the banks within which the experience flows. The people I portray project images and impressions of themselves which are neither hermetic, confessional, nor grounded in exaggerations of their personal ancestry. It all happens between the lines.

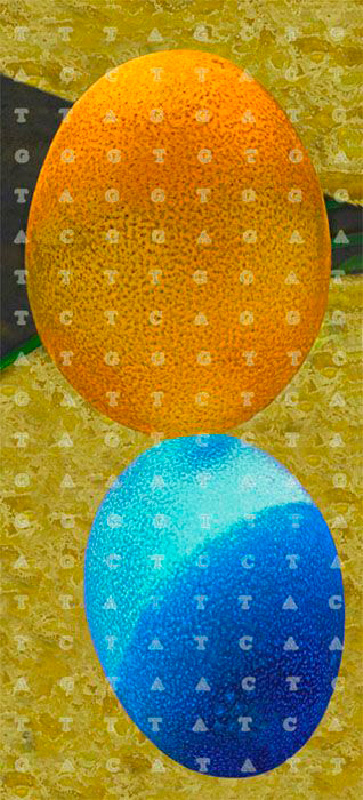

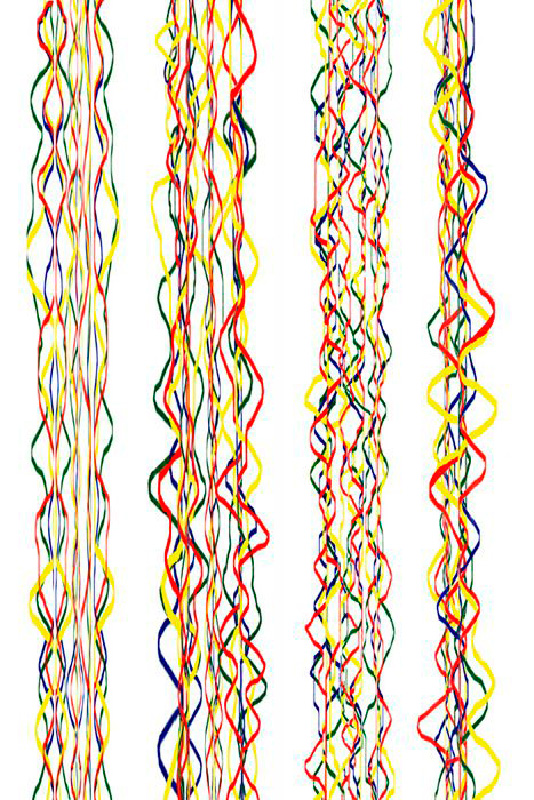

Speaking of all, we are all the product of generations of successful ancestry, going all the way back, and this fact of life is referred to by Native Americans as The Long Body. The Long Body is interpreted as an elementally enduring spiritual force, and is translated by our more materialist culture as a string of chemicals connoting the bases which form the DNA sequence and shall I say embody our physical inheritance.

In all of these portraits the supposedly objective identity of the individual is reconsidered and portrayed with a subjective motif. I substitute a literal representation of a sitter with a subjective pictorial theme I select, compose, and photograph. I subvert the traditional mode of photographic representation with poetic metaphor and suggestion. My portraits open up associative areas for interpretation that go far beyond simple identification. The images I compose grow out of my discreet and harmonious interactions with the subject/sitter…. What also connects these portraits is the apparently universal syntax of DNA sequencing and the supposedly objective quality of photography as well as a deeply personal approach that opens up the portraits in terms of a context for deliberately subjective and associative inferences.

Through an inversion process that informs my work, positive pictures become like negatives, the invisible is made visible through the genetic code, and the negative image is developed on positive photographic paper, all of which are inversions of the common approach to photography. It would be misleading to read this inversion as impacting only medium and technique. Above all, this process deals with attributes and their depiction as well as the myth of objective representation.

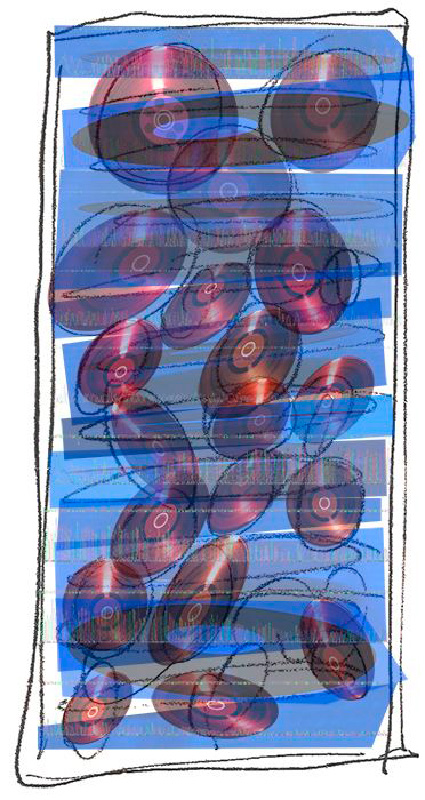

The early series, 1989-1995 included people I knew at the time and includes artists Jeff Koons, Peter Halley, Russell Maltz, Marion Zazeela and LaMonte Young, Ana Pellicer, Garance, Mel Chin, and Jacques Lowe, among others. This portrait of my late wife Janet, who died of breast cancer, was made in happier days, while this later portrait revealed darker portents yet celebrates her life nonetheless. None of these portraits were commissioned, nor was my multi-paneled Portrait of John Cage, 1993-1996. The work inspired Volker Rattemeyer, Director of the Museum Wiesbaden, to commission two sets of 13 portraits in 1997 for an exhibition date which happened to coincide with the millennium and unexpectedly, with the publishing of the human genome project.

The commission from the Museum Wiesbaden to create The Invisible Body allowed me complete freedom to choose and portray people from both The Rhein-Main region of which Wiesbaden is a part and my native New York. I employed the conceptual basis, the scaffolding, as it were, of Leonardo’s Last Supper: twelve portraits plus one Leitmotiv portrait establishing the major theme of the set. My 12 +1 theme for New York included portraits of artists William N. Copley, Charlemagne Palestine, Nam June Paik, and Merce Cunningham, Eiko Ishioka, and Miquel Algarin. I also dedicated an entire series to the American scientist James D. Watson, one of the discoverers of the double helix structure of DNA. Portraits of Rev. Al Sharpton and Dachau survivor Yakob Polishchuck were also of interest.

My series of 13 portraits made in and around Wiesbaden and Frankfurt is different. Famous names do not leap out from this series, as the region, while rich in tradition, love of culture, and deeply Germanic mythologies, and a financial metropole and home address of the Euro, does not foster an environment suited to celebrity. Here are portraits of Adolph von Ribbentrop, son of Hitler’s infamous Foreign Minister, Dr. Peter von Seck, Fluxus collectors Michael and Ute Berger, vintner Armin Diel, and German SDS founder and publisher, KD Wolff.

Midway through the project the museum ‘s budget was cut and the powers that be became more concerned with fundraising than in participating in defining the content of the exhibition. I retained complete freedom within my conceptual framework, and enjoyed that rare experience when the curators did not overly introduce themselves into the making of the art.

The problems I encountered were basic to most portrait projects: who do I choose to portray and how. The why had already been considered. My choices of subjects represented an ongoing definition of the project, a reordering and layering of meaning. As financial support materialized, my problems and issues reverted to exploring the possibilities within my projects’ parameters.

The success of the exhibition at the Museum Wiesbaden inspired a large-scale commission for a private bank in Stuttgart. The commission called for the creation of six portraits for a large atrium in the central core of the landmark building. I was again given complete freedom and money, though very little time. Christoph Berger of the Kunsthaus Zurich was a most supportive jury member, as was the architect Frieder von Berg, whose 60th birthday is being celebrated in Stuttgart in a few hours. I was to have been a guest of honor, but had already signed up for this talk. I can feel the commissions slipping through my fingers!!

The portraits commissioned by this corporate entity posed another set of artistic problems, particularly working with a tight deadline and finding ways to avoid the well-wishers and related people who try to help, offering opinions, names of possible subjects, unsolicited comments and suggestions which can be so enervating. There was also the very real architectural precondition- each of the six pieces was to hang on a large Pompeii red wall, one above the other in the dramatic atrium. Six disparate portraits had to be brought into a cohesive visual format with interrelated colors. The corporate environment forced cohesion amidst individuality.

This time last year I received an email, an artist’s dream, from Mr. Norbert Eckes of Wiesbaden and Berlin. He politely inquired whether my work was for sale, and recounted his experiences of my work and its effect upon him. He had been able to earn a great deal of money during the three years since seeing my work for the first time. He purchased a piece and we agreed to meet at the Frankfurt airport where I would deliver the artwork to him. I had an 8 hour layover between flights while returning to NY from ARCO in Madrid, where I had a disastrous encounter with an arrogant collector who had summoned me through my Madrid gallery Pilar Parra to discuss his infatuation with my doing a portrait of him, only to decide against it in a most dismissive manner. He was not interested in paying for an artwork he could not judge in advance. I was not interested in speculation.

Norbert, however, was very curious and became an ideal subject for my approach. The end result interested him far less than the process, which was the real artwork for him. The process, the set of encounters, coincided with a period of self discovery forced by an injury he sustained to his Achilles tendon in March. His feeling that a final photographic realization of this encounter was a bonus, the material artwork a secondary benefit allowed me to organize my reflections on Norbert into a focused though open- ended piece. I returned to meet him in Wiesbaden twice, joined him in Berlin for a few days, and completed the portrait at a photo lab in Wiesbaden in early September, having considered, met with, and reflected upon Norbert for six months.

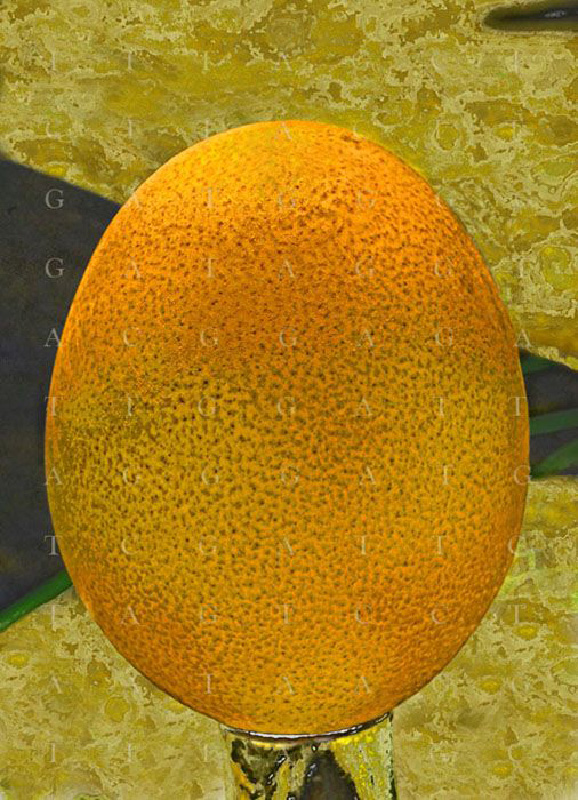

The visual elements in Norbert’s portrait are based on things he would either normally reject, or which he would not immediately associate with himself, yet he identified very strongly with the completed work.

I began by photographing a giraff at the Bronx Zoo. Each Giraff sports a unique array of brown spots. I retained the spots and allowed the white areas of the giraff’s skin to become transparent. I sliced a red cabbage in half and photographed the pattern made by the inner core. Here again the white areas within the cabbage allowed one to see another layer below that so that the giraff spots float like out of focus clouds, the cabbage seems like roads or indications of landscaping, and the green below appearing like vegetation. To create this layer I photographed the contents of a package of frozen herbs purchased from the frozen foods section of a grocery store.

The final effect of the piece is as if seeing a 3 dimensional illusion- like seeing a landscape while looking through an airplane window from a great height. The spots seem like clouds or islands but are integrally related, as they are the elastic skin of an individual animal. The piece is defined by the characteristic of combining what appear to be a set of unrelated floating elements and structures, seemingly random and unrelated while in fact, they are the very image of cohesion, seen at a distance. The DNA sequencing procedure is not the one I helped create in 1988 with Applied Biosystems, it is the more recent Variable Tandom Repeats, often used in Forensics, and modified and improved for massive use by the forensics team working on the remains of the victims of the 9/11 attack. The sequence was gleaned from the roots of a few hairs that I plucked from Norbert’s head, preserved in a clean baggie, and delivered to my DNA sequencing lab.

DNA

DNA Sequencing Technology

Malcolm D. McGinnis, PhD. Forensic Analytical Services, Inc.

Summary for Kevin Clarke, 9/11 WTC Project

Following is a summary of the technology used to generate DNA sequences for Kevin Clarke’s portraits using the hair samples from the WTC rescue workers.

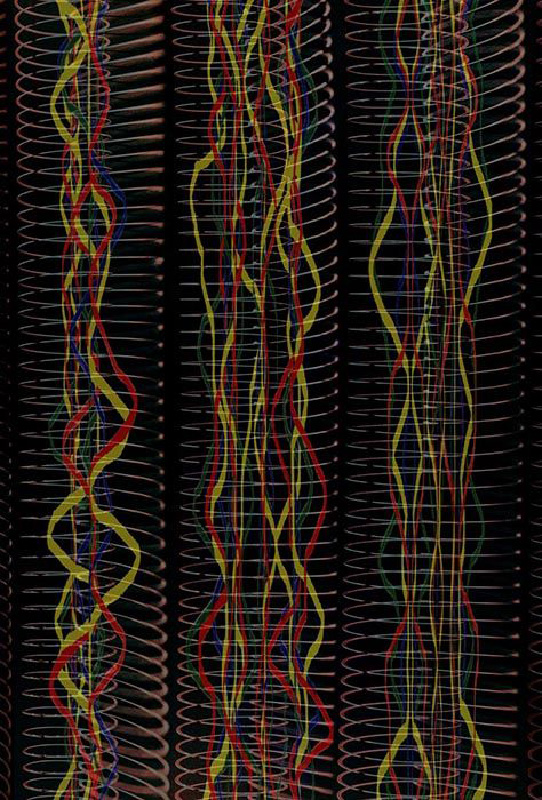

1. The Gene. The DNA sequences in Kevin’s portraits are from a gene named DRB1, coding for a human leukocyte antigen (HLA) protein, in a region known as the human major histocompatibility complex (MHC). The genes of the MHC are central to the immune system and participate as an integral part of the body’s ability to distinguish self from non-self. These genes determine the ability of the immune system to recognize the presence of foreign or non-self entities in the body; typically, these are bacterial or viral infectious agents. This recognition process helps to initiate an immune response involving many other components of the immune system and ultimately leads to clearance of the infectious agent from the body.

Our group at Forensic Analytical has developed a series of tests based on DNA sequencing for analyzing multiple genes within the histocompatibility complex. In addition to their natural role as part of the immune system, these genes have been shown to be directly relevant to the success or failure of bone marrow transplantation procedures for treating leukemia and other cancers.

2. Amplification of the Gene. The process of selectively amplifying the DRB1 gene from the total DNA isolated from the hairs is based on the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), a Nobel Prize winning technology developed in the 1980s. This technology has transformed all aspects of molecular biology that are used in biomedical research, diagnostics, as well as forensic and other identity DNA testing. The analyses that we performed on the hair samples were comparable to a forensic analysis in that limited sample material was available. The beauty of the PCR technology is that it enables analysis of biological materials that are present in very small amounts. For work such as this, avoiding invasive sample collection procedures is, simpler, safer, and enables distribution of samples without special shipping requirements; in this case, the hair samples were simply placed into overnight FedEx.

3. DNA Sequencing. The DNA sequencing technology used to generate the sequences in Kevin Clarke’s portraits is the same as that used to sequence the human genome. The application of this technology to routine testing in both forensic and biomedical research procedures is a result of a decade of improvements in instrumentation and biochemistry. Our group has spent 10 years developing these methods to the point that they can be used on a routine basis by laboratory technicians with minimal training. Not only are the sequence figures informative, they can also be visually interesting and appealing as Kevin has shown in his portraits.

Malcolm D. McGinnis, PhD

The article that appeared in The Journal of Clinical Chemistry:

In 1988 James D. Watson of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory and Paul Schimmel, who was at M.I.T. at the time, suggested that I approach the then small startup company Applied Biosystems, manufacturers of automated DNA sequencing machines. My need as an artist was to display and incorporate a freestanding, independently meaningful DNA sequence in a work of art. It was important for me to have access to a DNA sequencing procedure which was specific to an individual. I wanted to ship a blood sample to a lab and get a representation of the person’s DNA that was unique to that person. Such a procedure did not exist. Applied Biosystems contacted Cary Mullis, inventor of PCR, and spoke with researchers at MIT, CSHL, and other institutions. Paul Baird of Lifecodes, Inc was also helpful. Using my whole blood, which I supplied to Applied Biosystems, the team was able to create a new set of protocols and the result was an automated DNA sequencing procedure using PCR which analyzed the HLA-DQ alpha region of the genome. This is an area that has to do with the immune system, and which determines whether a foreign body is infecting the person. If so, the body defends itself. In order to make this determination, the body must be able to differentiate self from non-self. By sequencing this region, one accesses the part of the genome which tells the cells to be you. I was able to use this procedure for many years in my portraits without paying fees because I had contributed to its invention. My Self-Portrait in Ixuatio was the first opportunity to use this knowledge in a work of art. I received a printout of my DNA sequence months before the results of the experiment were made known at a scientific conference. The Journal of Clinical Chemistry published these results in the now classic article Automated DNA Sequencing Methods Using PCR. This paper has become a standard text for anyone who is studying biochemistry, genetics, etc.

Scheduling

Please contact me to schedule an appointment or to discuss a project. Thank you.