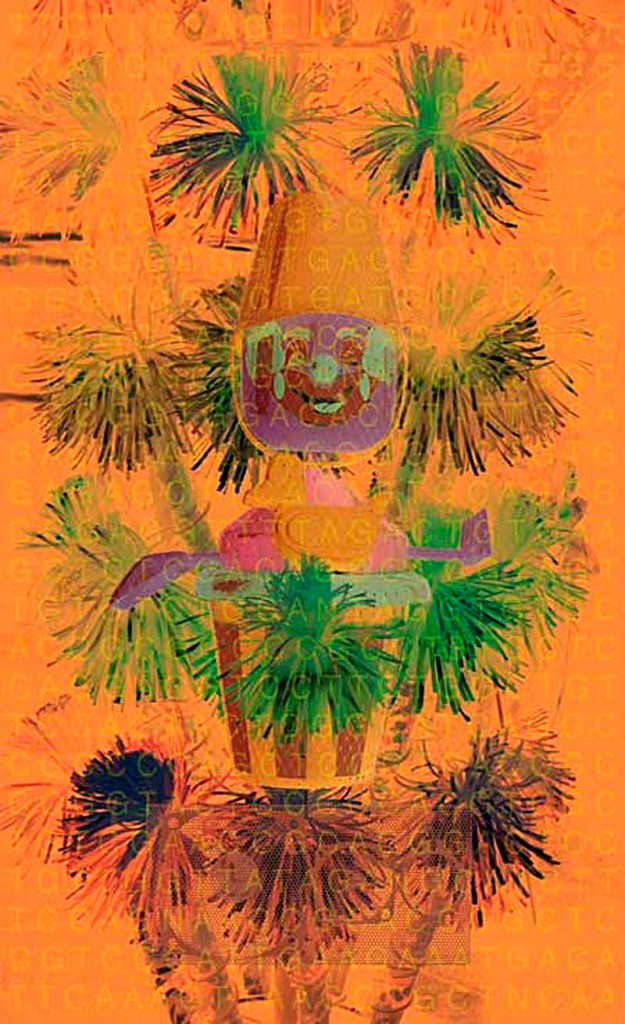

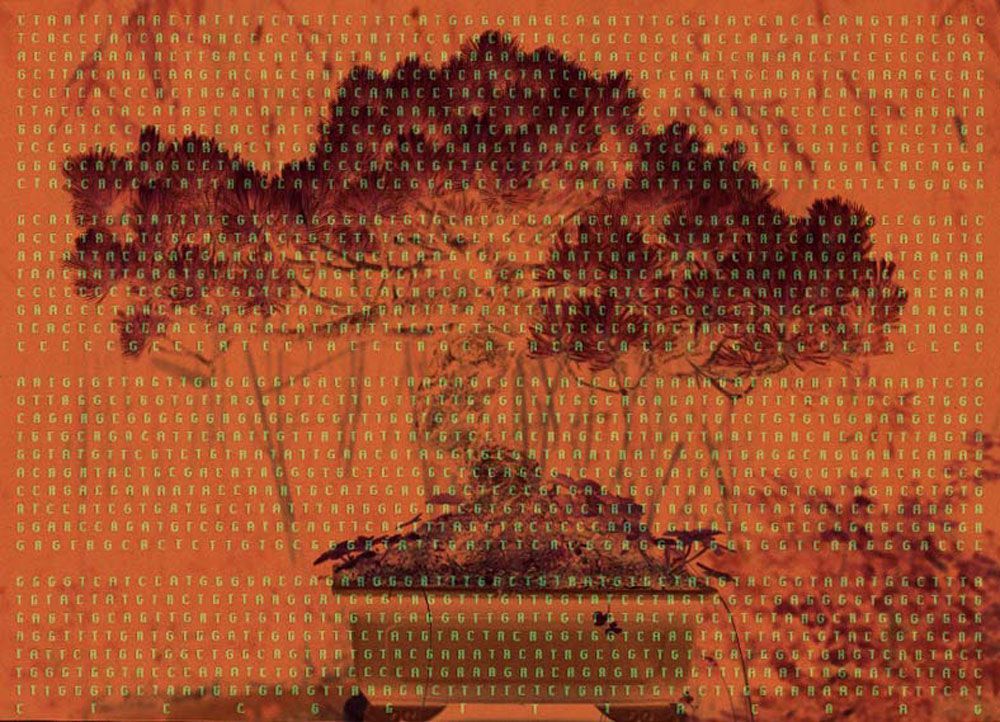

The Invisible Body, (Der Unsichtbare Körper) was an exhibition I made for the Museum Wiesbaden in 1999-2000. The 26 portraits were made between 1998-1999. There were 13 Portraits of people chosen from New York and 13 from the Rhein-Main area, mostly Frankfurt and Wiesbaden. One of the 13 people from each region was selected as a “Leitmotif”.

James D. Watson discovered the double helix form of DNA in 1953 with Francis Crick. Ute Berger represents the Rhein Main region. Please read the interview:

Interview with Kevin Clarke

Interview with Kevin Clarke, conducted by Museum Director Volker Rattemeyer and Chief Curator Renate Petzinger as they prepared the catalog.

Tape 1

Q: You are describing your experiences with the people you are portraying; what’s going on with them, what are they feeling?

A: Perplexed, curious, a bit at sea.

Until recently, I’ve worked with people I’ve known well, people who have been aware of the process by which I approach making a portrait. I came to Wiesbaden and allowed some time to get to know the city, the people, the specific character of this city, the city as cell. I’ve thought of the city as Italo Calvino considers a city, in Invisible Cities. Twenty years ago I experienced Frankfurt and North Hesse, specifically, of course, Kassel. I have portrayed friends from this time, Claus Bury and K.D. Wolff, people I’ve known for many years. There are others whom I met during my months in Wiesbaden in 1998, the Lahls, Von Ribbentrop, my neighbors, and then there is Ute and Michael Berger, whom I met in late summer 1998 and stayed in close contact in both New York and Wiesbaden. We’ve worked together intensively and I’ve learned a lot about the history and mythologies of the region; Romans, water, Niebelungen, Siegfried, Odenwald, Taunus, Brunnen, Jawlenski, Fluxus. With each of these people there is a different relationship, some deeper than others.Generally, my approach to the people I portray comes as a surprise to them. Later it seems quite natural. I choose people because they represent an aspect of the city I need to look into. Sometimes I invite them with a formal letter, sometimes I approach a subject at dinner or in a social environment. In every case, this initial approach is crucial, for if they show discomfort or disinterest, it’s over, I make no further effort, no pursuit, because I am also requesting a blood sample. I begin with first impressions and begin to dig deeper. By giving a blood sample, which I call a drawing, the work becomes an interaction, a collusion. The person is giving something of themselves. I begin to think of the person differently, perhaps there is a subtle shift in responsibility. I begin to think about them more, to meditate on them, it’s an empathic experience.

One example is the portrait of Prof. W. Fresenius. He is a person who engages concrete experiments with parameters created to yield concrete results. They make sense. While he also encounters uncertainties, they are viewed within clearly defined parameters, boundaries are set. He has shown some interest in this project from this very standpoint. None of us was sure what his portrait would be- neither myself nor the subject, nor the sponsoring organizations- it’s totally open. The content is unknowable in advance, this is why the subjects are often perplexed, curious.

Q: Do you tell what the metaphors (images) are going to be..?

A; Not at all. It’s an open question until the very end. It’s pointless for me to indicate how I’m going to visualize them. I do not overlay a preconceived idea or define the person by their profession. I try to experience the person and to field, in the sense that a ball player fields a ball- I’m fielding images the person is projecting. This is happening on a subconscious level. Sometimes I stumble across an image while photographing, finding by doing rather than by thinking.

Of course there are themes in people’s lives. Adolf von Ribbentrop has always had to confront history. He represents an important historical period by birth. His father was Hitler’s Foreign Minister. This is his burden and yet it is only a part of him. The piano tuner/ builder Yakov Polishchuk was in camps in Austria and in Dachau under the Nazis, and again in the Ukraine after the war under Stalin. Munira Nusseibeh’s father was the last Arab mayor of Jerusalem, yet her brother is writing the peace accords.

During the drawing at my Karlstrasse studio last summer the nurse I had hired became restless and decided to go home earlier than planned. The cab driver who had helped us prepare the event by driving us around town collecting foods, furniture, etc. had stayed on for the event, curious. When Charlemagne Palestine arrived a bit later, the nurse had left as had two prominent doctors. The cab driver, Michael Hartmann, revealed that he is a medical doctor, practicing in the north, and visiting his family in the house he grew up in, across the street from the studio. He expertly drew a blood sample from himself, then, with a fresh needle, from Charlemagne. Despite this theme of coincidence, the accidental visitor who by chance saves the situation, I did not employ chance as the theme of his portrait.

It’s interesting to me to hear the responses subjects have for their portraits.

Q: Is there any relationship between the “Couch Project’ and your portraits-perhaps in the way that on the Red Couch you have a person…

A: The red couch was a kind of macro-world project, a survey of a country and it’s cliches. The working title was Americans on a Red Velvet Couch,, an acknowledgement of Robert Frank’s classic, The Americans. The couch functioned as a parenthetic device, it separated and isolated the people in their environments. It was an early post-modern event piece, a series of theatrical happenings which challenged the truths of documentary photography. Nevertheless The Red Couch was a familiar form of portraiture, the person in the environment. In August Sander’s time people were less media savvy, manipulated their images less. They simply looked into the camera. The presence of the couch debunks this literalist, documentary mood. The Red Couch is also a pre-photoshop project. We actually transported the sofa tens of thousands of miles. This is now unnecessary.

My current work explores portraiture and retains a social dimension, but it is more about the individual mediated through codes- physical and pictorial codes rather than media codes and cliches. This work is invasive, blood is used, and the person’s persona goes deep inside me, allowing me to reflect upon the person, to muse. The social body is linked through biochemical comparisons, by shared feelings about genetic issues. I have more freedom in this project, I can make a still-life, a landscape, photograph a shadow or a mysterious or obvious object, it’s all possible.

The subconscious power was located in the couch, an inanimate object. It dreamed, we watched. In this new work dream and portrait bleed together.

Q: How do you find this metaphor for the person?

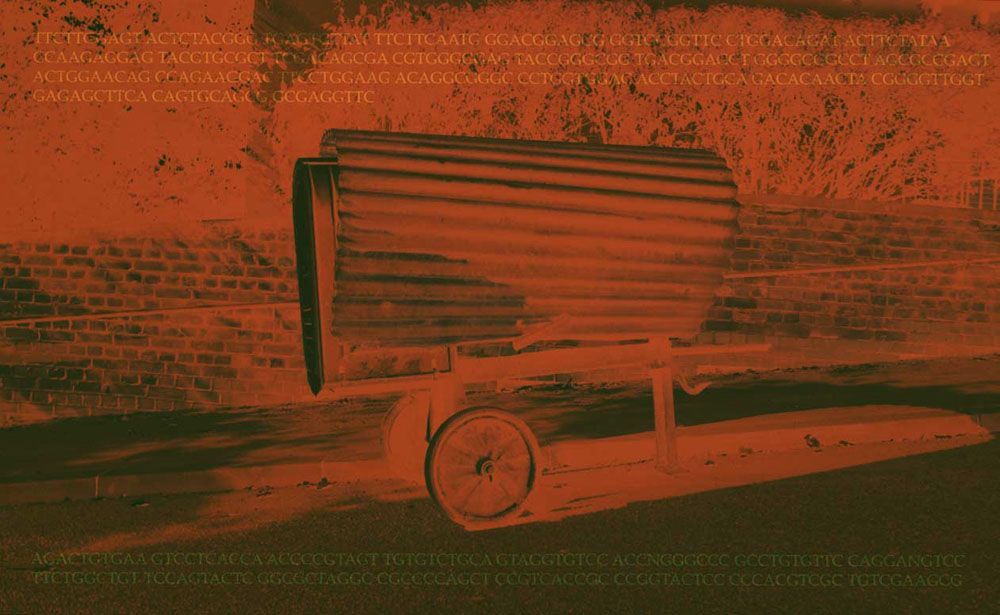

A: K.D. Wolff, for example. He is a publisher, founded the German S.D.S. Students for a Democratic Society, an Adorno-school Frankfurter, from Fulda, I think, father a judge. I am aware of his appearance before the House Un-American Activities Committee, Senator Strom Thurmond, the same Committee that deported Berthold Brecht. I am aware of transformations in his life, his important Hoelderlin facsimile editions, the recent Kafka facsimile edition of The Trial. He represents a view of German culture that is very much respected in the world. Knowing these things about K.D. helped me to see an old cement mixer in a different way. It’s a cement mixer from this optimistic post-war period, hidden under a large pine tree (tannenbaum) with a brick house behind it. I asked the owner if I could drag it out into the street, and the Indian cab driver Deepak helped me to place it in a more open spot. I saw the machine as an object of transformation. You put in elements of sand, water, lime and publish streets, houses, walls, architecture. It reminded me of Beuys’ Honey Pump. It was a forgotten machine, and it reminded me of the peculiar conversation I had with K.D. and Michel Leiner, also of Verlag Roter Stern/ Stroemfeld, of their experience after the fall of the Berlin Wall. A few weeks after the wall fell, their backlog was worthless. People were no longer interested in these themes; the student movement, women’s movement, socialism vs. capitalism. The facsimile editions are quite sought after, but the public had changed.

Q: Have you had responses from people who have been portrayed?

A: My preferred response is that they recognize themselves in their portrait. My earlier portraits were mostly of artists, people who use their imaginations professionally.

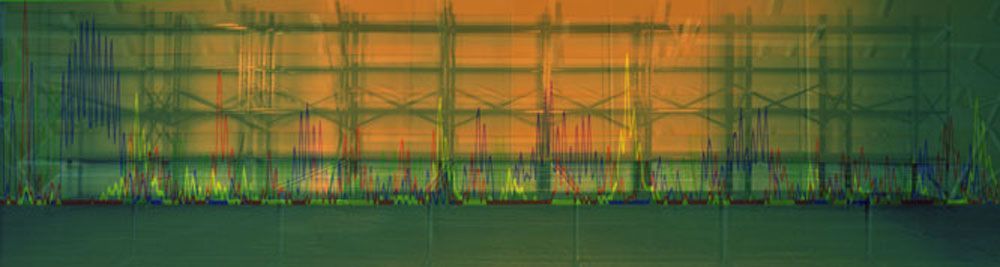

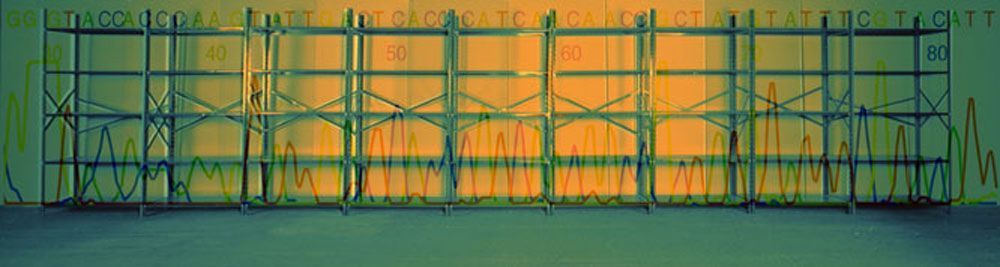

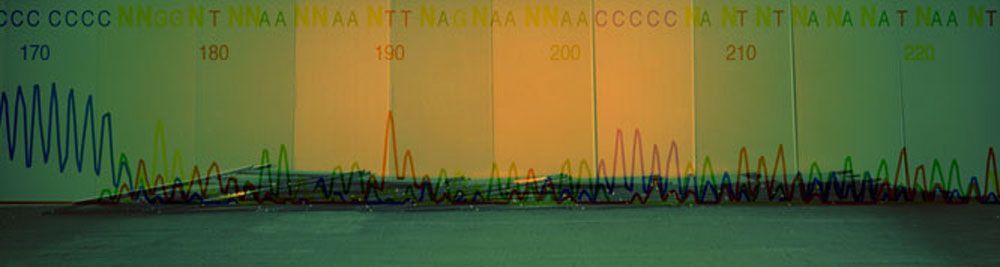

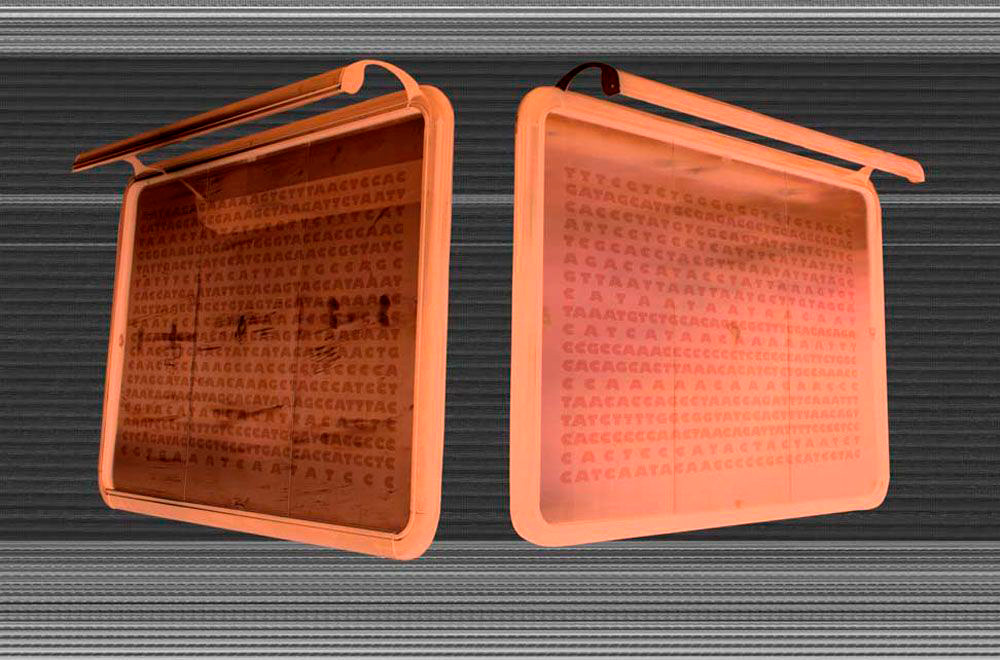

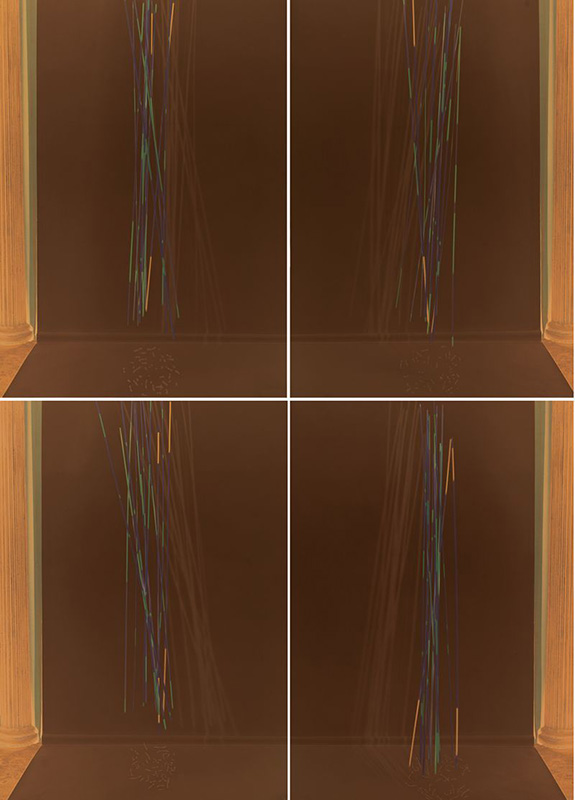

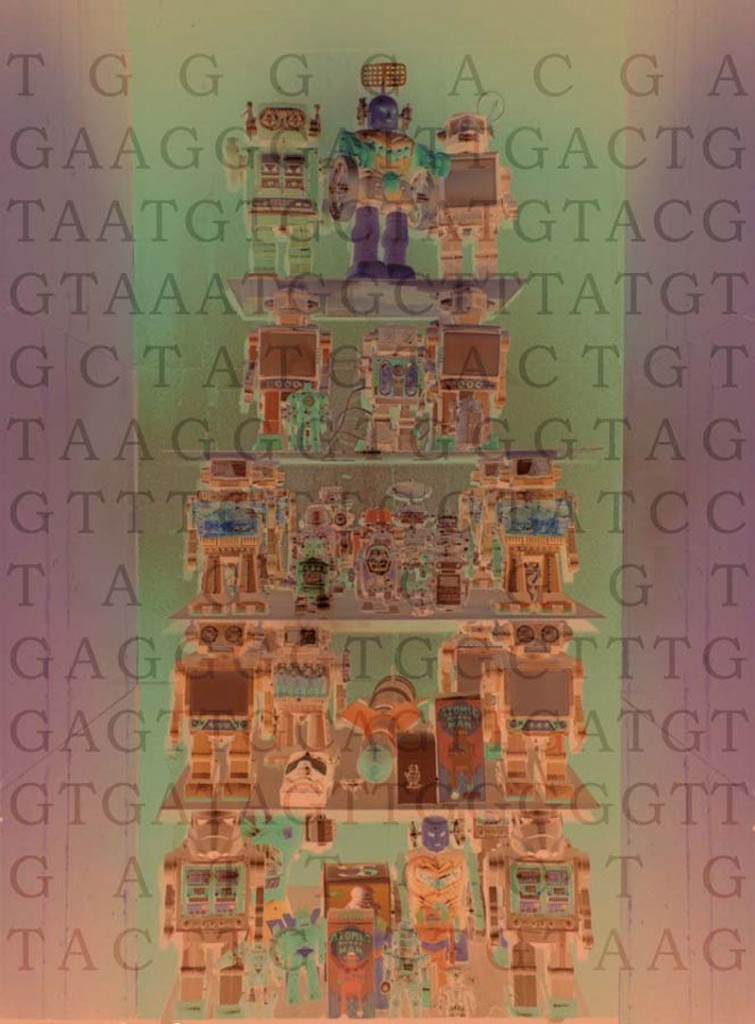

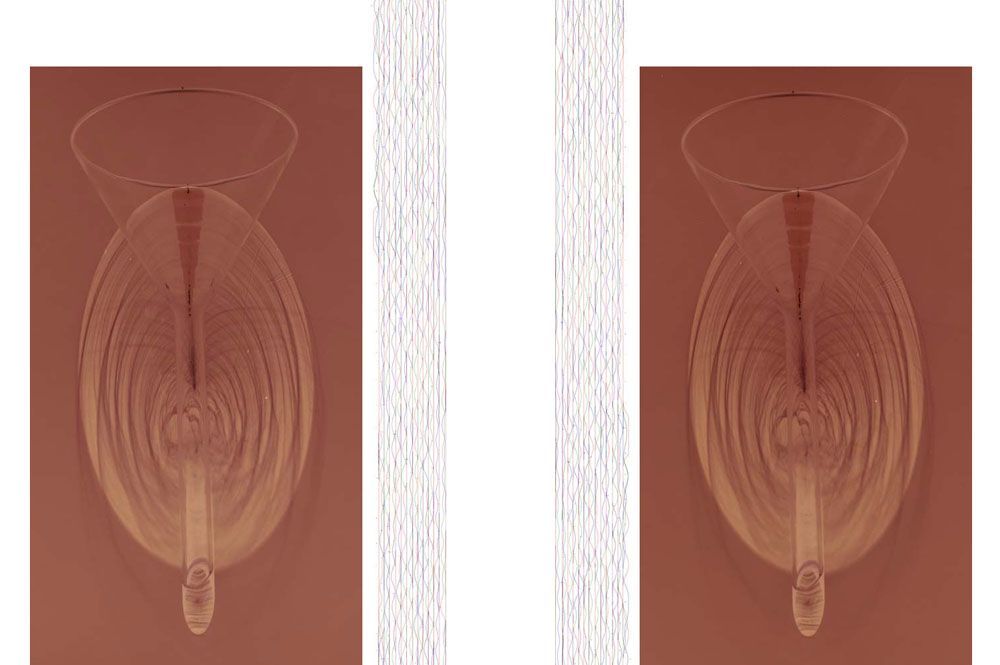

Recently James D. Watson visited me in my studio and saw transparencies of his portrait. He was very open and curious and readily understood the motion of the shelves, a wave-like, helix movement of shelf units. It was clear that I was basing his image on structure, his and Cricke’s unique discovery of structure, the double helix shape of DNA. My direct knowledge of him was minimal: telephone conversations, letters, his autobiographical recounting of the discovery in his book, The Double Helix. I’d visited the lab he founded at Cold Spring Harbor, NY. He invited me to visit him at home for a day. Upon reviewing this portrait, structure re-emeged as a theme. It has a lot to do with listening.

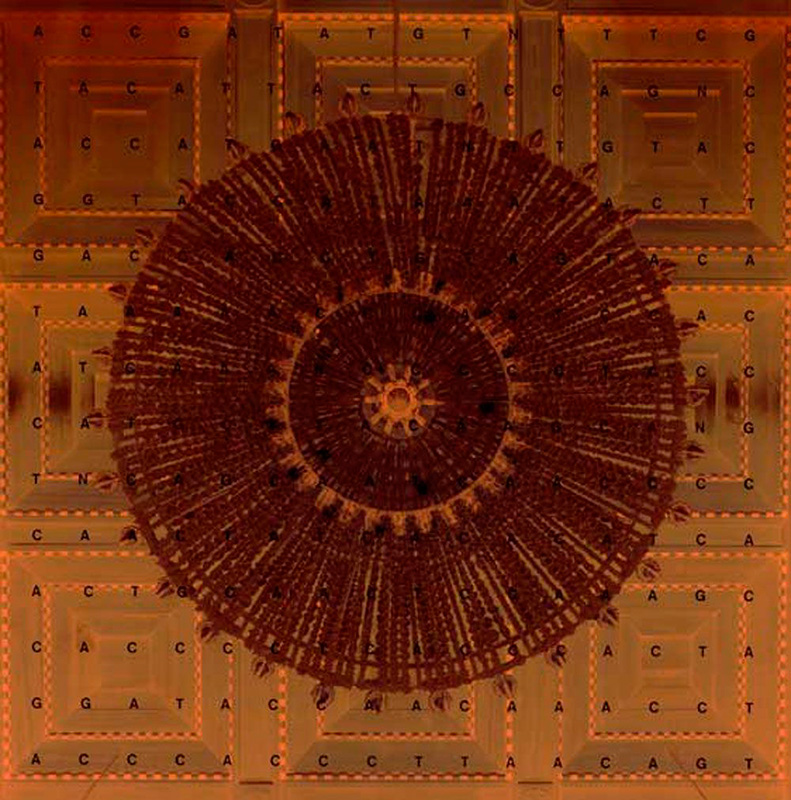

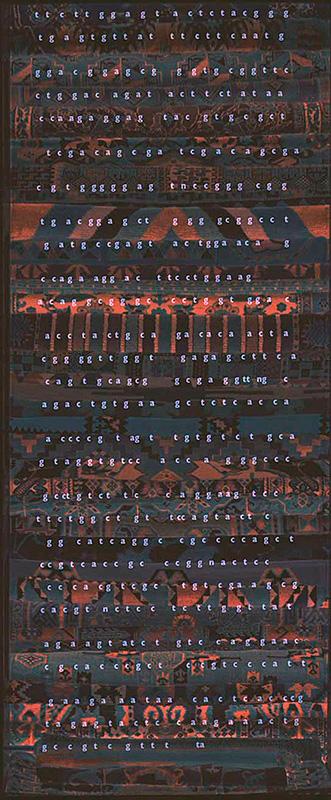

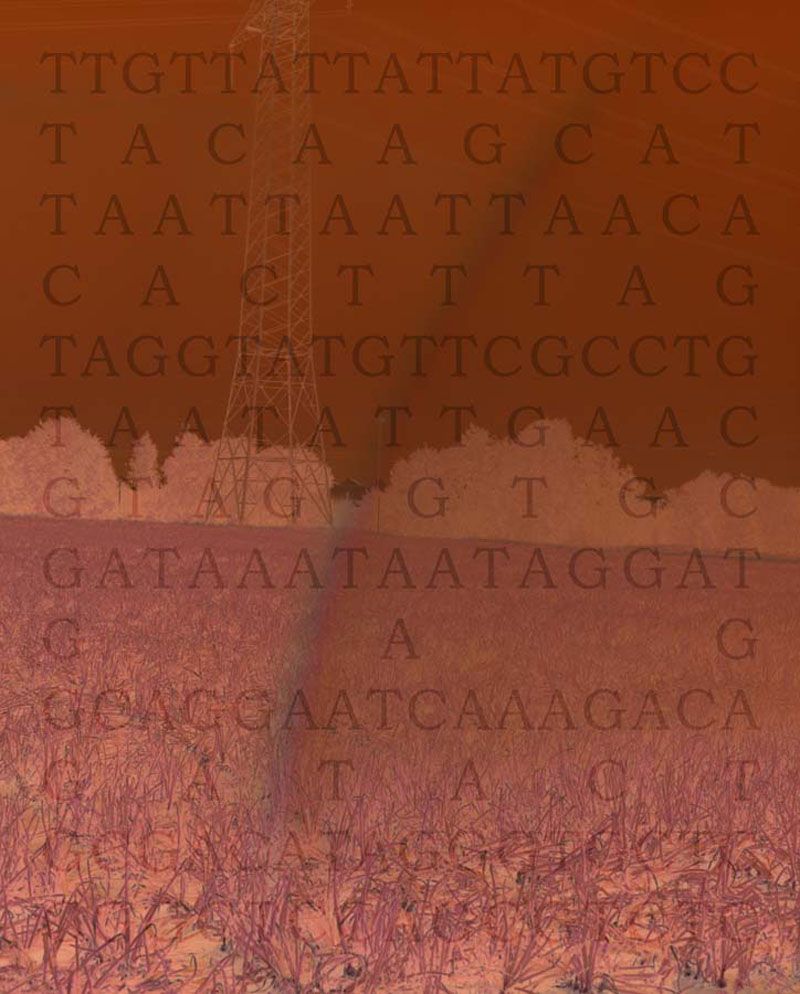

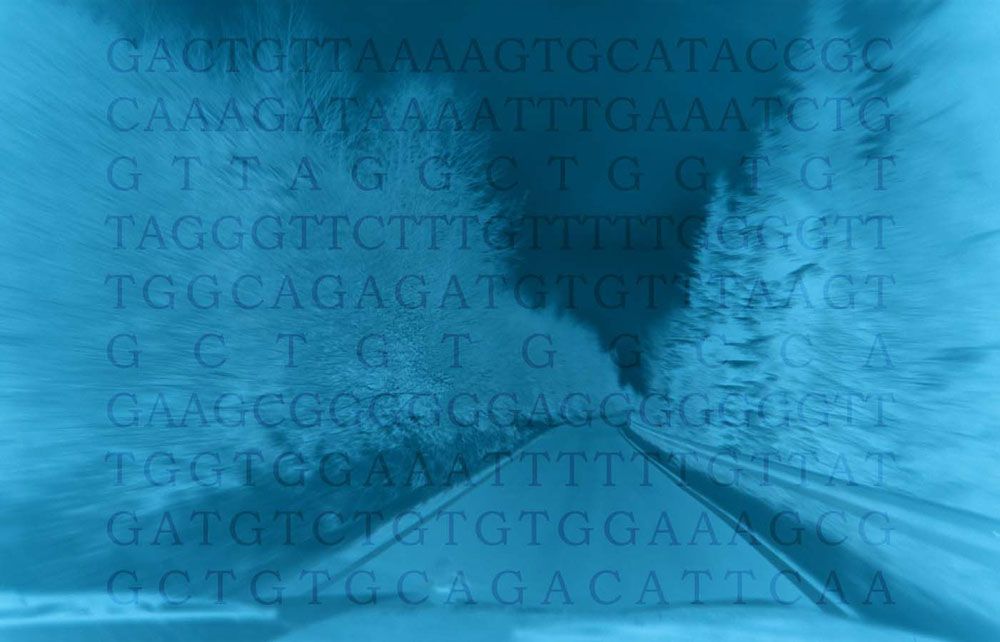

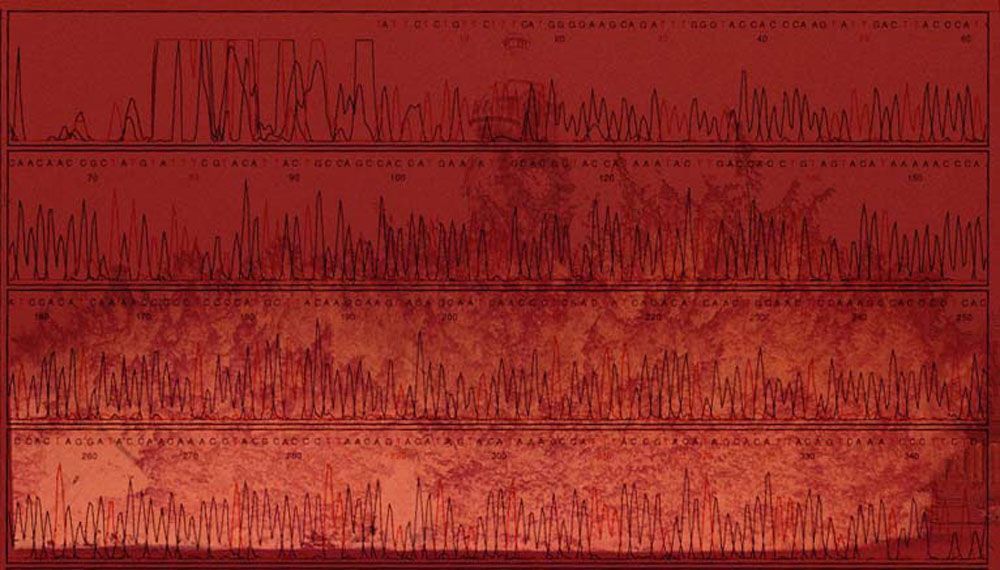

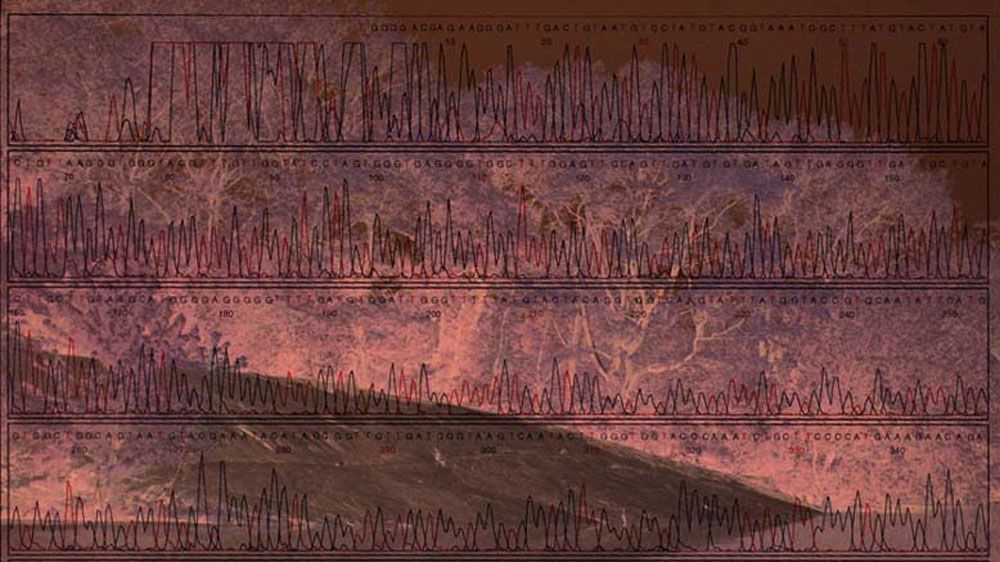

Q: In your finished portraits I notice you sometimes represent the genetic fingerprint as a line, a pulse, or as a series of letters. What criteria do you use to decide this? Is there a connection between the person portrayed and the formal solution? Does this depend on the motif you’ve chosen for the person?

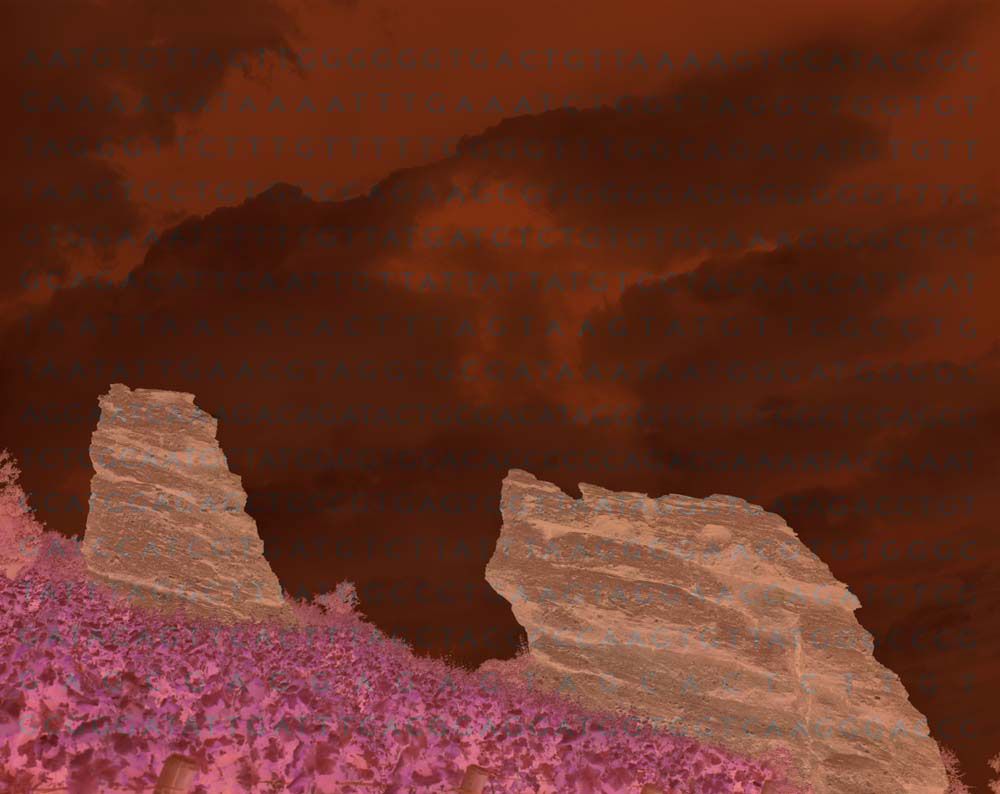

A; I get a feeling from the person and that is represented in the motif and the graphic approach. Sometimes I want an energy pulse to course through the image, as in the portrait of John Cage (1993-95), which has seven panels. The portrait of Merce Cunningham has only chromosomes, splattered on the floor of a stage as if dropped from a pipette, the lab tool used to drop the chromosomes onto a slide. I choose a certain font for each portrait, decide on it’s prominence. Some fonts are more reserved, some are sans-serif, etc. The images from Prof. Fresenius’ portrait require contemplation, they are similar, but different. Anna George’s more musical. Some are arranged like instructions to a product, or like an advertisement. In the portraits of Michael and Ute Berger the graphic solution supports a narrative line, holding the images together.

Q: Janet’s portrait, a vase, flowers…

A: This was a picture I put together very quickly and spontaneously while she was in the room. I received a vase in the mail from the Tampa Museum of Art. I was asked to make an artwork from it – they could auction to raise money. I did not like this request very much…I turned the vase upside down, noted the circumference of it’s base, and found a vase with silk Dutch tulips which I’d hung on the wall, tulips pointing outward. I already had her DNA sequence on acetate so I removed this from my files and taped it to the screen of my view camera while composing the image. I sent the museum a print of this “candid” portrait, and later enlarged it to a greater size. My printer called me and mentioned an irregularity, the crack in the lip of the flowerpot and asked whether we should retouch it. Of course not. It had been a hopeful image to us during her pregnancy, but later, we noticed it was cracked directly in the area of the breast, when one views the image figuratively.

Q: What was your first portrait of this kind?

A: The self-portrait in Ixuatio, which I did after returning from Mexico after completing a photo reportage for Geo magazine. I was covering the Day of the Dead in Patzquarro and recognized this shot as a self portrait when I made it.

In the mid Seventies, as a student, I did a project for Yoko Ono, building copies of the great pyramid at Ghiza.Tents, models, etc. My payment was a trip to Mexico to view the pyramids. While in Mexico my appendix (blinddarm) broke and I barely survived. When I revisited Mexico ten years later for Geo, the Day of the Dead experience was an apotheosis. As the women left the graveyard at Ixuatio at dawn, I photographed them through the haze.

Shortly thereafter, Applied Biosystems, Inc. created the sequencing procedure I used in the early portraits. I had asked genetic research scientists I knew to create a non-comparative, individual-specific DNA sequencing procedure. They chose the HLA-DQ alpha region of the genome and, using my blood, experimented. The result was important, first published in the journal Clinical Chemistry Vol.35, Number 11 in 1989. Today, synthetic blood is used. It’s more predictable, less dangerous and cheaper. As I was the supplier of blood, my DNA sequence was the first, so I used it in my self-portrait. The portrait with balloons of Janet was next, then I had a drawing in my loft, including Ana Pellicer, of Mexico (Copley’s Magritte tree), which was the third.

Q:What was new about this process?

A:This procedure was the first significant non-forensic approach, non-comparative. It stood on it’s own. The part of the genome which tells the cells how to develop is brought to light. This crucial area helps distinguish one organic form from another, one individual from another.

Q: For what did you need this procedure which was created for you?

A: My portraits are not based on comparisons. I needed a representation of the person’s genetic reality that had independent meaning when included in a picture. Dr. Paul Schimmel, of M.I.T. suggested we find and develop sequencing procedures which would be state of the science for that period, so a portrait from 1991 has the most highly developed sequencing approach for it’s time, and in 1999 we used a few new approaches as the year progressed.

Q: Where is this used now?

A: A most interesting project by Dr. Mary-Claire King from Boston who went to Argentina and worked with a human rights group, the Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo. By comparing the mitochondrial DNA of the grandmothers and of the children of “disappeared” enemies of the junta, King was able to reunite families. The children were growing up in the families of the ultra-right, their parents having been murdered. She later worked on a forensic project in El Salvador, identifying remains. Then she began important research on hereditary breast cancer. Tissue typing is also used extensively by the military to identify body parts. Such a contract is quite lucrative… The early procedures are used for tissue typing.

Q: Did you get any royalties?

A: No! I had access to the technology while it was relevant.

Q: The Leonardo idea…

A: I read a biography of DaVinci and was excited about his experience as an artist, and chose to focus on his commission to paint The Last Supper. He was working in his studio in Florence when he was invited by messengers from the church Santa Maria della Grazie to come to Milan to paint a painting for the dining room. This is the one room where the priests gathered daily to eat together and it was important to remind them of why they were gathered together. They were a powerful and competitive group of men whose job was to transmit the will of God as seen by the Pope throughout Christendom, they were broadcasters of the Pope’s message. He had two and one half years to complete the painting. For the first two years he visited the room in which he would paint The Last Supper daily, sat and stared at the wall, and left without touching a brush. Evenings and afternoons he coursed through Milan , making lightning sketches of people he saw, snapshots, really. He’d make a quick sketch to capture the features and gestures of people, then develop the drawings later.

It’s important to know that he had worked on de Devina Proportione, The Divine Proportion with the mathematician Fra Luca during the four years previous to this commission. He had absorbed the leading geometry of his time while drawing the illustrations for the book. The composition of The Last Supper incorporates this geometry transparently. One must look at it, as scholars have for five hundred years; the painting is not just a group portrait with twelve apostles and Christ sharing the dinner preceding his capture.

I found this to be an interesting format. Twelve portraits plus one, science and art, portraits and genetics, A Last Supper for Wiesbaden, A Last Supper for New York… It became an organizing principle for me, which has nothing to do with the Christian message of Leonardo’s painting. I have not been comparing the people portrayed in this work to the apostles.

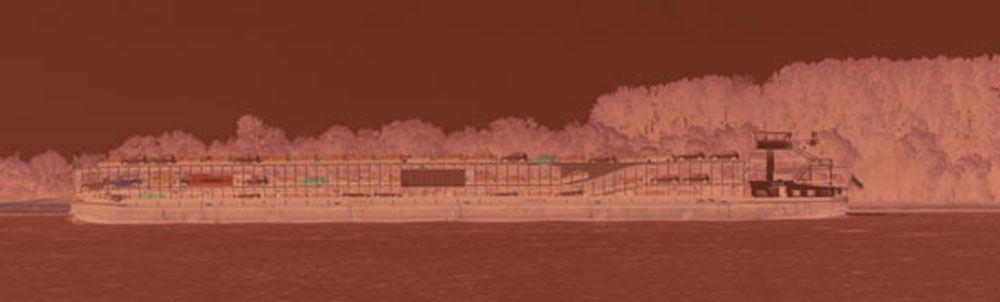

By regarding the city as cell I can explore the functions of various chemical transactions which occur within the cell and compare them to the roles people play in their cities: transformers, agents, broadcasters, protectors, chance, architects, generators, etc. This is why I’ve chosen Watson as the leitmotif image for New York. Ute Berger was chosen for she represents cellular memory, a conscious and subconscious development of her grandfather’s role in Wiesbaden.

Q: (not on tape)

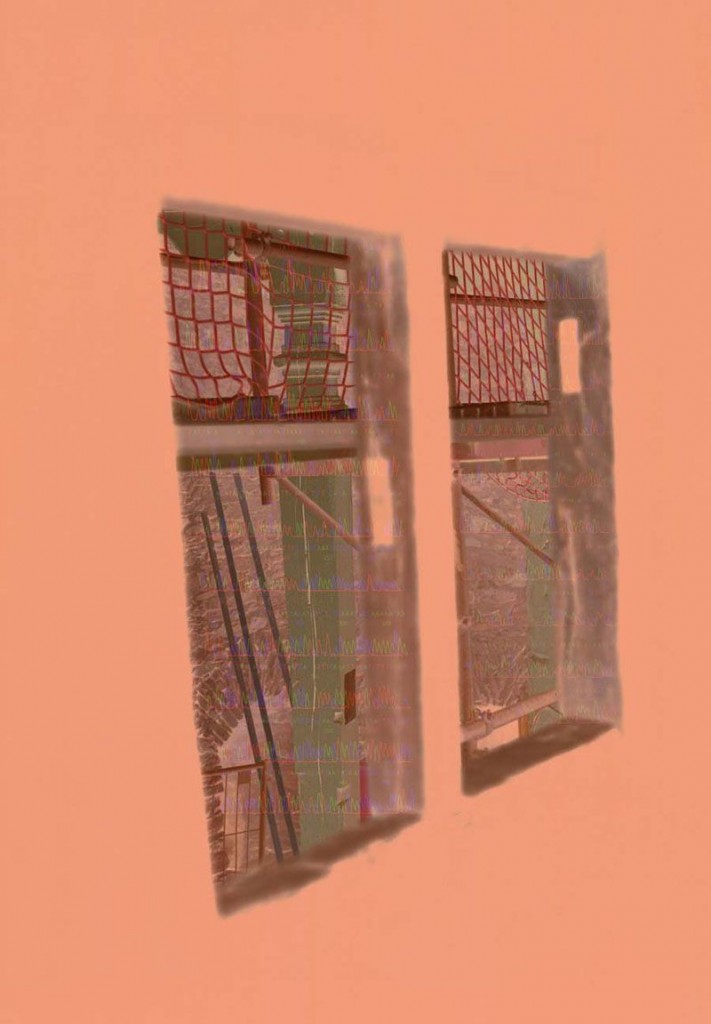

A: Viewing the pictures technically, I decided to work in the opposite way I have previously. Instead of putting the person in front of the camera I use a coded representation of them. I shoot with a color negative and retain the negative as a positive. I sometimes employ cross-processing, manipulations in the negative and, recently, computer manipulations.

My everyday experience includes sweeping through the city with an openness which allows me to sense people and objects in a kind of interaction, with an open heart, filtering. I practice seeing inverted colors. It helps me to be patient.

Q: There is normally a big symmetry in the pictures…

A: I like this frontal, iconic view. I also prefer vertical compositions to horizontal. They are like standing people. I’m not shooting crowd scenes. A sequence is a series of units, so the repetitive unit attracts me, for example in v. Ribbentrop’s portrait, or Anna George’s.

Q: Are there important artists or photographers who have influenced you?

A: The unimportant influenced me more, but for purposes of autobiography, the great ones seem to get all the credit. I did not learn photography, I studied sculpture and some architecture at Cooper Union , which meant I had two influences. One was Hans Haacke who questioned everything and introduced us to the German artists of the Seventies; Beuys, Staeck, Rinke,Vostell, Fluxus. Rene Block’s was our favorite gallery. I met Beuys and saw his great shows there. I was impressed, went to Basel to meet him again in Fall, 1976, experienced the documenta 6 and his 100 days of the Free International University at the Friedericianum. I was selling Kunst und Medien , our collaborative anti-catalog.

The other direction was sculptor Christopher Wilmarth’s minimalism. I worked for Al Held and Sylvia Stone as Sylvia’s assistant for those three school years. I built Sylvia’s sculptures and crates, and helped install her room-sized sculptures of plexiglas. I studied architecture with Peter Eisenman and one photography class with John Kender, who, with Harry Schunk had made the great photographs of the Nouveau Realistes, including the montage of Yves Klein’s leap into the void. We learned nothing technical, shot slides and talked about seeing things. Surrealism, Man Ray, Copley, came later.

I learned photography by doing it, mostly by making mistakes.

Q: You have the metaphor, you have the picture, and you have the DNA sequence.

A: There are different ways that I bring the images together. Sometimes I photograph the original graphic that I receive from the research lab. The labs include Perkin-Elmer/ Applied Biosystems, Agowa, AG, New York University Medical Center, and Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Sometimes I use the letters that represent the bases of the DNA, using various fonts. I collage these elements together, sometimes stacking many sheets of film. On occasion I combine cross- processed film with negative film or negative film with transparency, etc.

Q: What are your future projects?

A: I am going to continue exploring these ideas in such a way that the next project will bring me information that changes how I see things. I am interested in working with the confluence of digitalization and humanity,

Q: What about your thinking of the ethical dimension of genetics?

A: The human genome project and developments in computer and life sciences are leading to the digitalization of the human being. Complex interactions between areas of knowledge and technologies are redefining how we perceive ourselves, first medically, then socially. Greater transparency means less privacy. Gene therapy will transform medicine, extending life. We are facing another great spin of the wheel.

As gene therapies cure diseases and alter cells to extend life there will be more people, longer lives, with predictable effect on the environment and food and water supplies. French farmers are already rioting in response to innovations in food technology, especially the American-made genetically manipulated seed stock. Farmers have been manipulating crops and livestock without controls since Mendel’s time. Today’s changes have brought about public awareness and the beginning of advanced investigations into the effects of agricultural r + d. (research and design).The population explosion continues, except in parts of Europe and the former Soviet areas.

In Germany, however, the birth rate continues to fall. Couples wait longer to have one or perhaps two children. This creates heavy expectations for that child. If life sciences can give a family advantages, my bet is they will use them. In countries in which the health system is paid for and controlled by the government, payments will become a social issue, with wealthier parents employing gene therapies privately to gain advantages for their progeny. Will people come with labels describing them as GM people (genetically manipulated)? Will this create a new form of racism? Are people willing to embrace Faustian solutions for private enhancements? Think of human growth hormones for athletes and the image conscious.

The mechanical interventions; blood transfusions, organ transplants, hair replacements, artificial limbs, synthetic veins, organs, among others, are only creepy for those who don’t need them. The other side of this coin, the mechanistic view that one is what one eats {Feuerbach) is really what scares people today- eat a drug which facilitates pregnancy- get sextuplets. Eat genetically manipulated food- your hereditary engines are transformed. The need to nurture and care for each other is a driving force in vitro fertilization, gene therapies, and much drug research. People make choices and pay for them.

The mullahs are already up in arms. The speed of change scares people. That yesterday’s super computer is today’s laptop sounds quaint. The marriage of computers and biotech, the de-coding of the human genome and that of other species, informatics and the notion of a person as data enhance our ability for active internal intervention. Who expected people to carry telephones with them all day long? To watch television and computer screens at work and leisure? The all-pervading anomie? People fear the answer to the equation today’s clone is tomorrow’s….?

These are casual observations. Some people trust humanity, others do not. Long range- I’m optimistic. These are mostly physical issues. Is the soul touched?

Renate, I would like to talk about some more of the pictures, the portraits, shall we talk about this on the telephone and communicate by email? Now there are more completed portraits. Shall I talk about them or would you like to write about them? I am sending new images this week and next...K