1977-1980

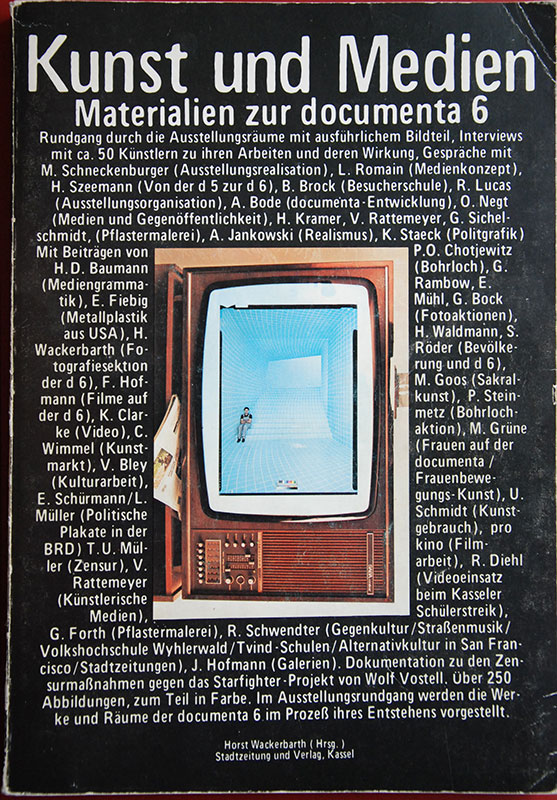

KUNST UND MEDIEN, Materialien zur documenta 6

Published by Stattzeitung und Verlag, Kassel, 1977. Clarke worked with a small group of local students to create an anti-catalog that was published 3 days after the exhibition opened. The book featured 300 pages, over 200 photographsin color and black & white, and important critical texts by Volker Rattemeyer, H.D. Baumann, and Rolf Schwendter. Clarke conducted interviews with 90 artists, including Joseph Beuys, Nam June Paik, Les Levine, and Jochen Gerz. 44,000 copies of the book were sold during the 100 days of document 6.

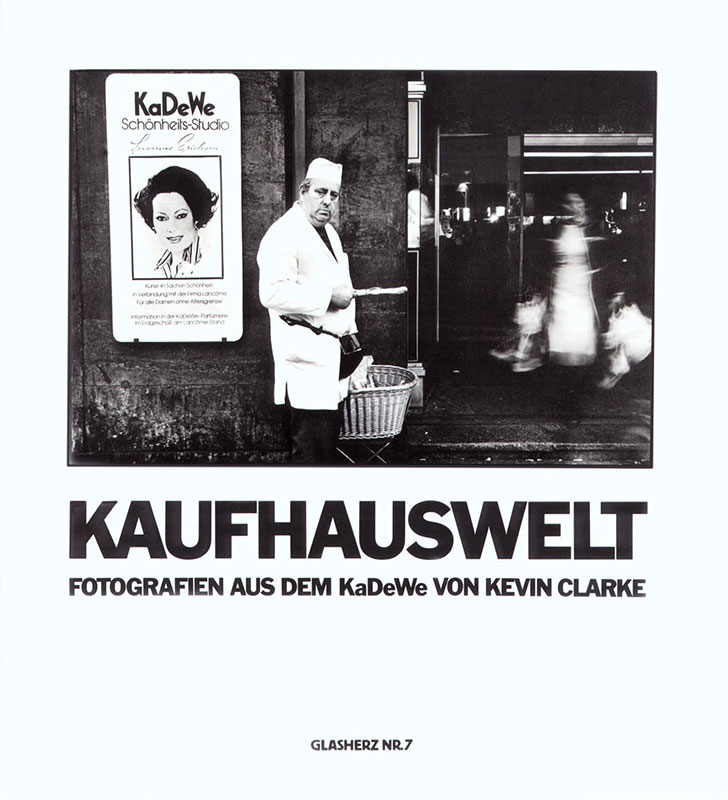

KAUFHAUSWELT (Department Store World)

Published in 1980 by Schirmer + Mosel Verlag, Munich. Black & white photographs by Kevin Clarke in Kaufhaus Des Westens (KaDeWe) in West Berlin. Text by Hans J. Scheurer.

“Close the doors of a department store. Open them again after 100 years and you have a museum of modern art!.”

-Andy Warhol.

In 1978-79 Kevin Clarke photographed each department in the West Berlin department store Kaufhaus des Westens, Department Store of the West. Then newly renovated, the KaDeWe, as it is known, was the largest and most exclusive store in then divided Berlin. Using a Leica 35mm camera and a tripod, Clarke photographed the products, salespeople, and their presentation. The 72 images build a subtle view of the salespersons and the sales interface that is by turns ironic, idiosyncratic, humorous, and deeply revealing.

The series was first exhibited at the Frankfurt Kunstverein in 1980. The German philosopher Wolfgang Fritz Haug, author of Critique of the Commodity Aesthetic, (Suhrkamp, 1972) wrote an introductory essay for the book. It was rejected by the publisher, Lothar Schirmer, who is also one of Europe’s great art collectors. The impact of these photographs is currently being re-appraised by art historians in Germany and the U.S.

1995 — 2005

Tertulia and From the Blood of Poets

Tertulia includes portraits of Janet Hasper, Ana Pellicer, Jeff Koons, Richard Milazzo, Garance, Marian Zazeela, and LaMonte Young, among others. In 1993´95 I completed the Portraits of John Cage and Merce Cunningham.

“Coming as it does in the wake of long voyages and investigations, the recent work of Kevin Clarke has now set it’s course on a voyage inward, following the charts which both the mystic and the scientist have set down. These works constitute a “conceptual art” in the truest sense of the term.” by Alan Jones

KEVIN CLARKE by Alan Jones

Art is about names: knowing the right ones, making one for yourself. The naming of a child constitutes the common man’s sole poetic publication in the course of a lifetime. The name Iovanna on a church wall is all that remains of a life ended long ago, an unbreakable code. Today a humble name accumulates endless identification numbers, on passports and credit cards, accompanied by a recent photograph or even fingerprints; in the near future, “automated DNA Sequencing Methods Involving Polymerase Chain Reaction” will provide a more reliable way of confirming identity than knowledge of one’s mother’s maiden name. The “invisible made visible through an apparently simple genetic alphabet” in the words of the artist Kevin Clarke.

Portraiture is central to Clarke’s enterprise, intuitive meditations on identity and essence, body and soul, the self and the name. After having studied sculpture under Hans Haacke and Christopher Wilmarth at The Cooper Union, in New York, Clarke began a long and intense sojourn in Switzerland and Germany in 1976, and began his exploration of the innately sculptural attributes of photography which continue to this day. Clarke participated with Joseph Beuys in the Freie Universitaet during the sixth documenta, and Beuys was to sponsor Clarke’s inclusion in the International Artist’s Gremium. Beuys’ concrete approach to the apparatus of photography has left it’s mark on the younger artist’s own outlook.

Clarke’s book Kaufhauswelt , published by Schirmer & Mosel in 1980, can be said to be the first fruit of this influence: a classic of it’s kind and winner of the Kodak Book Award, it represents a sociological description of a large Berlin department store in the form of a series of black and white photo portraits of it’s employees. The Red Couch, A Portrait of America, followed in 1984. This book consists of one hundred color photographs of a cross-section of American citizenry, each subject seated on the same tattered red couch which the artist lugged across the continent to provide a metaphorical unifying thread of Buster Keatonesque surrealism throughout the volume.

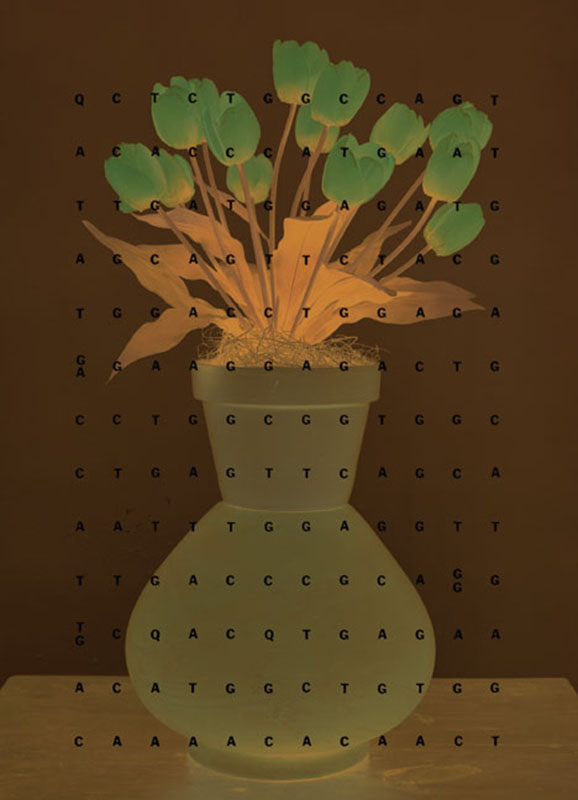

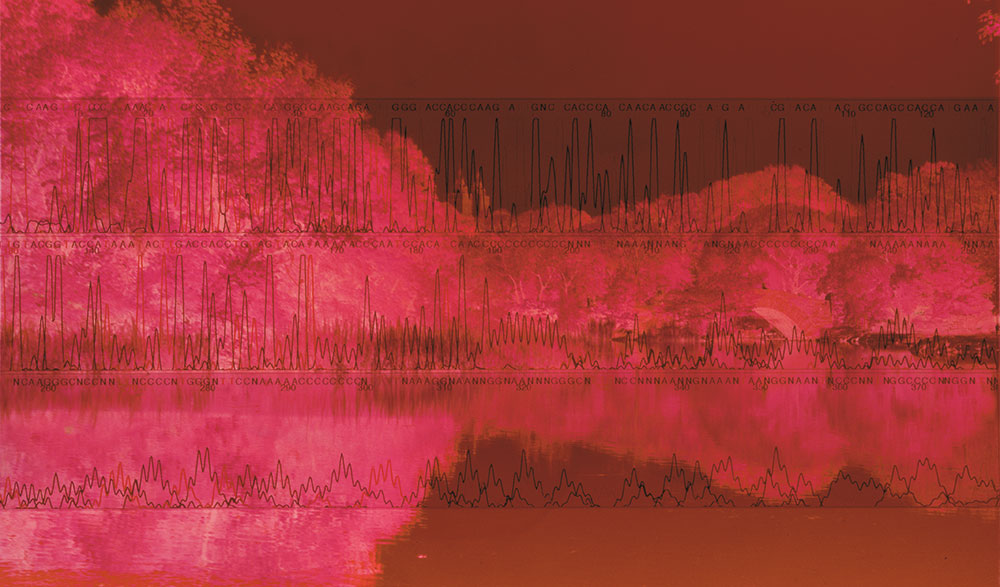

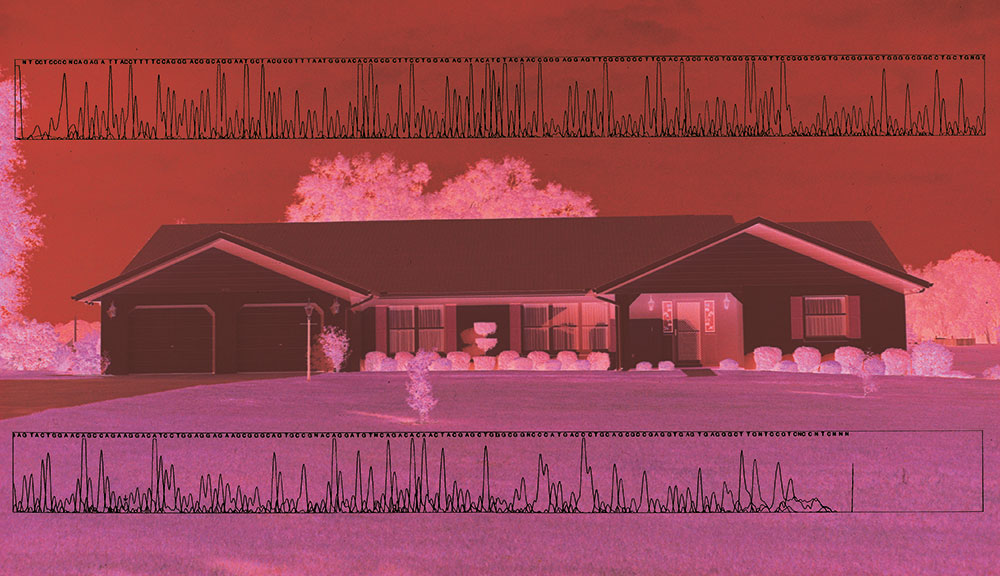

Today, Clarke is midway through an ambitious undertaking which consists of using the state of the science DNA sequence as a medium for portraiture. “My recent works investigate questions of Identity and the Portrait,” the artist has written. “One of the more obvious questions motivating these works is: What are identifying elements and when do characteristics coalesce into a unit which signifies “Portrait”? My activities in portrait photography suggest to me that other disciplines than photography as practiced have advanced investigations into identity and it is with this in mind that I have begun a number of collaborations with genetic research scientists resulting in genetic models embodying the notion of Portrait.”

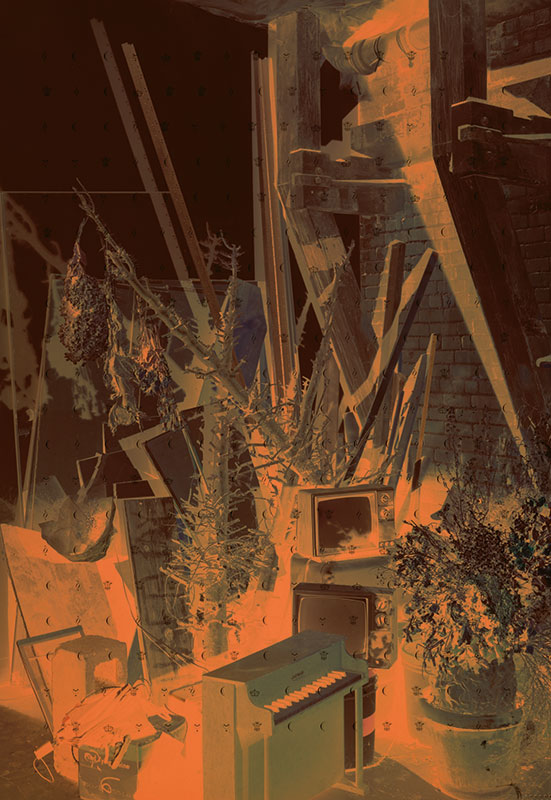

It would be a mistake to conclude that Clarke has fallen on his knees before the Golden Calf of science, although his attitude toward it is still far more earnest than Duchamp’s gentle mockery. Clarke still retains an essentially surrealist outlook , laced with a major dose of “Awe,” which is also the title of a world-ranging photo project tracing Halley’s Comet over all continents. A tree in one work is repeatedly referred to as “Magritte’s tree” by the artist, and the actual spreading chestnut in question has it’s roots deep in the soil of William Copley’s Connecticut estate-fertile ground for surrealism; a low-lying suburban house in another work was chosen by personal, intuitive motives, and may bring to mind both the content and working process of second-generation surrealist and first-generation Pop artist Richard Hamilton.

At all times the presence of the genetic code remains, in these works, a reminder of the mysterious, the ungraspable, always out-of-reach goal of the search for knowledge of cosmos, and of self. The DNA becomes an invisible cathedral, an architecture whose purpose is to lead to the contemplation of the divine. “The scientific novelty may be fascinating, the social implications of genetic engineering may fill some with dread, but as an artist what interests me and moves me is the confluence of notions of individuality, language, physicality, and the development of a codex to describe a most elusive reality.”

Coming as it does in the wake of long voyages and investigations, the recent work of Kevin Clarke has now set it’s course on a voyage inward, following the charts which both the mystic and the scientist have set down. These works constitute a “conceptual art” in the truest sense of the term.

The above text by Alan Jones was published in Teme Celeste, Spring 1993

PORTRAITS WITH A FOCUS ON THE INVISIBLE

An aspen stand of seven thousand trees in Colorado, a typical small forest of extraordinary beauty, is found to be a genetic expression of a single individual – like seven thousand hairs on the head of a person. A genetically uniform underground cloud of thirty acres swimming a couple of meters beneath the forest is found to be an individual fungus- again, like hairs, the mushrooms which appear after the rain are but brief expressions of a single giant organism which has existed since the Ice Age, inhabiting an obscure plot in Michigan.

Today, notions of individuality, tribe, and nation are changing in fundamental ways, not only through intermarriage of previously distinct groups and through social and personal strategies of re-identification, but through organ transplants, gene therapy, chemical and genetic manipulation of the fetus, and other crude forms of genetic intervention. Test-tube babies and in vitro fertilization are manifestations of our need to nurture and to further life. It is the function of culture to watch carefully and to be aware of how these experiments interconnect with other forces that define our age.

In my current portraits, the physicality of the sitter is introduced by combining their DNA sequence or chromosomes with an image I create with a camera. I do not arrive at the image by putting a person in front of the camera because, in point of fact I photograph the image with the person in mind, after reflecting. The work is a visual elucidation of my musings about the person, elaborated through the selection of a theme and inclusion of details of my choosing.

My approach to portraiture is open. The person is not defined, captured, or categorized. The portrait evolves as an attempt to understand the invisible body in an expansive, sometimes iconic vision. They are experimental interactions; poetic, mediumistic, synthetic. Taking a clue from cell biology, my subjects can be perceived as transmitters, receptors, enablers, or transformers.

Portraits of people I know well have been loosely grouped in a series I call Tertulia. These blood samples have been taken at my home or studio, an event not without drama, particularly for those giving blood for their portrait. From The Blood of Poets proceeded from a less intimate knowledge of my sitters. This group includes a number of people in the arts who are of interest to me and include poets, writers, or musicians.

In May, 1992, while working on this project I visited composer John Cage and choreographer Merce Cunningham with a registered nurse, Reiko Saito. The two men had agreed to my wish to make an experimental portrait that originated from their DNA. I had done conventional portraits of Merce in the past.

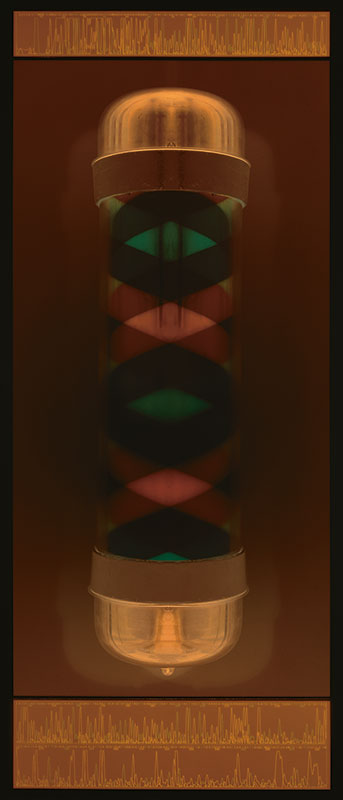

Blood samples were taken from them by nurse Saito and rushed off to Applied Biosystems, the manufacturer of DNA sequencing equipment and chemistry that has been processing my DNA samples since 1987. I had prevailed upon leading genetic research scientists, including James Watson from Cold Spring Laboratory, Sandra Wolman from the Michigan Cancer Research Center, and Paul Schimmel from M.I.T. to create a highly individual-specific DNA sequencing procedure in collaboration with the research lab at Applied Biosystems. The procedure has since been updated and my blood work remains state of the science as the years go by. Exploring the HLA-DQ alpha region yields a representation in graphic form of the part of the genome which tells the cells how to develop.

Additional samples went to Dr. Mary Ann Perle at the cytogenetics lab at New York University Medical Center. The chromosomes of Cage and Cunningham were isolated, photographed, and karyotyped by the lab supervisor Myra Craven. The DNA was isolated, amplified, and sequenced by Ann Shirkey and Anne Wan at Perkin Elmer/Applied Biosystems.

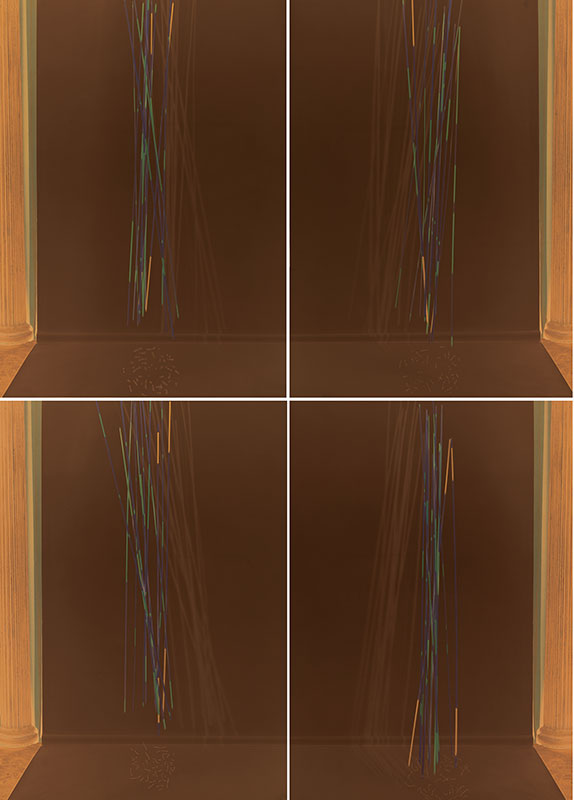

Representations of these DNA sequences and chromosomes were later combined with images to complete the portraits. The portrait can include a single panel, a room, or a series of rooms exploring a single portrait. A series of like images or of vastly different images could also form the basis of the portrait. In the Portrait of Merce Cunningham, four images of falling mikado sticks are combined with four separate photographs of Merce’s chromosomes. The chromosomes achieve their shapes from falling from a pipette and the sticks are caught in flight.

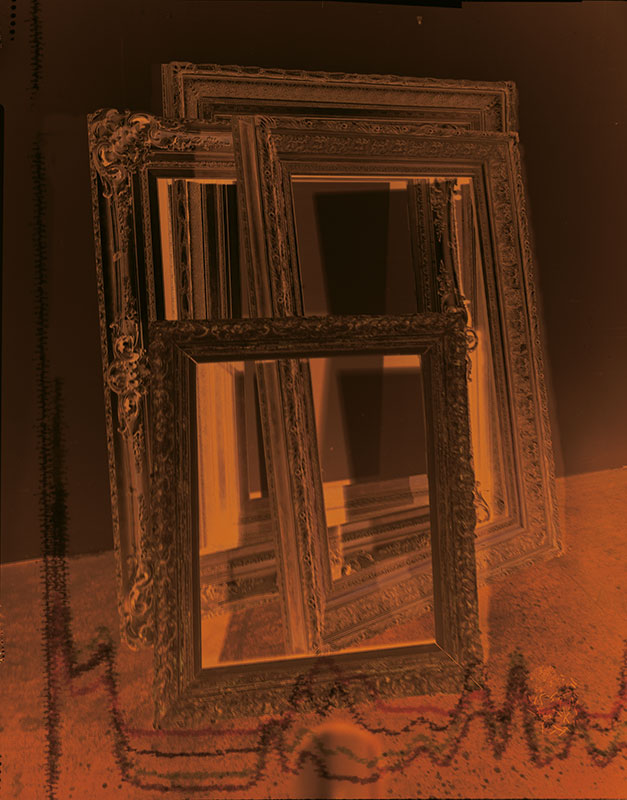

The full Portrait of John Cage includes ten 68×48” panels. For the exhibition at Curt Marcus Gallery in 1996 I photographed a selection of rare 19th century American gold frames, stacked and restacked against a workshop wall. The frames were somewhat randomly combined, with each of the panels featuring a different combination. Cage’s chromosomes appear differently in each panel and a DNA sequence runs in a continuous stream throughout the bottom of the ten panels. The frames are shuffled, and reshuffled, as is the framework.